The 5,000-year-old Ivory Man surprised scientists: it turned out to be a lady

[ad_1]

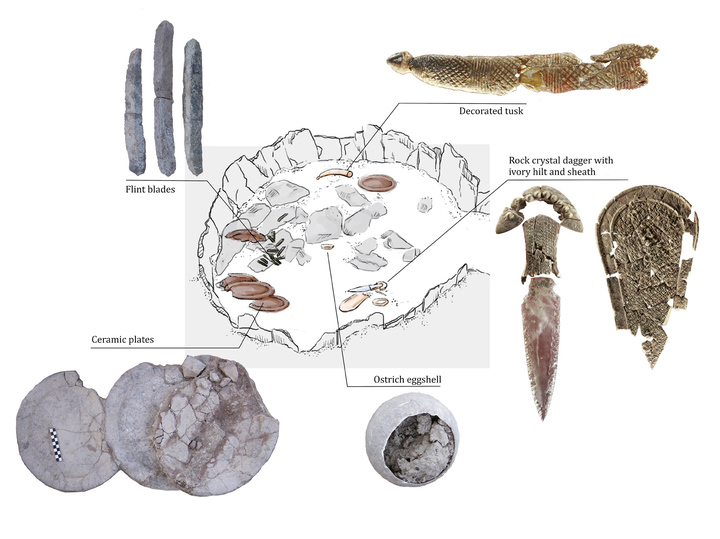

The remains, discovered in 2008 in a tomb near Seville, Spain, buried along with an ivory tusk, an ivory comb, a crystal dagger, an ostrich egg shell and an amber-encrusted flint dagger, clearly once belonged to someone important.

According to CNN, based on analysis of the pelvic bones, the specialist initially identified the 5,000-year-old skeleton as a “probable young male” who died between the ages of 17 and 25. A team of European archaeologists dubbed the remains the “Ivory Man” and began to examine what they called the “impressive” find.

More than a decade later, in 2021, researchers used a new molecular method to confirm the sex of a skeleton as part of a larger study of the find, and they were shocked. It turned out that the “Ivory Man” was actually a woman.

“It came as a surprise. So, it actually made us rethink everything about this place,” said study author Leonardo García Sanjuan, professor of prehistory at the University of Seville.

What they have learned about this woman and the society she lived in opens up a new window into the past and is likely to cause many to reconsider traditional ideas about prehistory.

“In the past, it was not unusual for an archaeologist to find remains and say, ‘Well, this man has a sword and shield. Therefore, he is a man.’ Of course, it is deeply erroneous, because it is assumed that in the past gender roles were the way we imagine them today,” said Garcia Sanjuan, “We think that this method will open a completely new era in the analysis of the social organization of prehistoric societies.”

A new method for sexing old bones, first used in 2017, involves analyzing tooth enamel, which contains a type of protein with a sex-specific peptide called amelogenin that can be identified in a lab.

Analysis of the teeth revealed the presence of the AMELX gene, which produces amelogenin and is located on the X chromosome, indicating that the remains were female and not male, according to the study.

Other studies have also used this method to dispel the “hunter man” cliché that influenced many ideas about early humans.

The typical way archaeologists determine the sex of a skeleton is by looking at the pelvis: in women, the pelvis usually has wider openings than in men. The problem is that the pelvic bones – compared to some other parts such as skulls – are thin, which means that over time they become brittle and easily crushed. That’s why it’s easy to make the mistake of looking at the pelvic opening to determine biological sex, as in the case of The Ivory Lady.

Ancient DNA can also determine the sex of human remains, but it is fragile, easily contaminated, expensive, and often impossible to extract from damaged bones, especially in warmer places. Amelogenin, however, is well preserved, meaning that it could be widely used to determine the sex of even incomplete skeletons.

“Now it is used more and more often. It’s a bit explosive and it’s exciting,” said bioarchaeologist Rebecca Gowland, a professor at the University of Durham who was part of the team that pioneered the enamel method.

“We’re testing the limits… and seeing how far back in time we can go,” says Gowland. Moreover, she added, this method can be applied to both adult and children’s teeth and is especially useful for the latter. This is because it is impossible to determine the sex of baby skeletons until they reach puberty.

The authors of the new study, which was published in the journal Scientific Reports on Thursday, believe that the ancient “Ivory Lady” held a high position and was revered by the society in which she lived for at least eight generations after her death. According to radiocarbon dating, the graves of dozens of people and other objects surrounding her grave date back to 200 years after her death.

The grave goods, including the objects with which she was buried and some, such as a crystal dagger, which were added later, are the most valuable of those found in more than 2,000 known prehistoric burials discovered in Spain and Portugal. No male tombs of similar status from that era have been found in this region.

The only relatively luxurious tomb in the region, containing at least 15 women, was found about 100 meters from the tomb of the “Ivory Lady” and is believed to have been built by people who claimed to be descended from her. According to the study, this suggests that women held leadership positions in Iberian Copper Age society at a time when a more hierarchical society was beginning to take shape in Europe.

The authors of the study say it is unlikely that her high status was given to her by birthright, since there are no children’s burials in the region containing grave goods. They believe that the “Ivory Lady” achieved her status through her own merit.

“She must have been a very charismatic person. She probably traveled or really had connections with people from distant lands,” suggests Garcia Sanjuan. He added that another source of her influence could be esoteric or magical. She had high levels of mercury in her bones, which could have come from burning or using cinnabar, an intoxicating substance.

“There is not a single burial (in the region) that could even remotely compare with the ivory woman in terms of the wealth with which she was buried. Neither woman nor man,” said Garcia Sanjuan.

Although the biological sex of the skeleton is not disputed, Gowland cautions that nothing is known about the gender identity of the Ivory Lady, and scientists should not impose modern gender norms on past populations.

“Perhaps they had some special status that was more significant than their gender identity, or … there was no binary gender system,” she noted.

Pamela Geller, assistant professor and bioarchaeologist at the University of Miami, agreed: “I think this Lady Ivory study confirms what feminist bioarchaeologists have been saying for almost two decades…that past socio-sexual life was diverse and difficult.”

[ad_2]

Source link