Journalists spoke about a village completely built from tombstones

[ad_1]

At first glance, Ami-dong appears to be an ordinary village in the South Korean city of Busan, with colorful houses and narrow streets set against the backdrop of mountains.

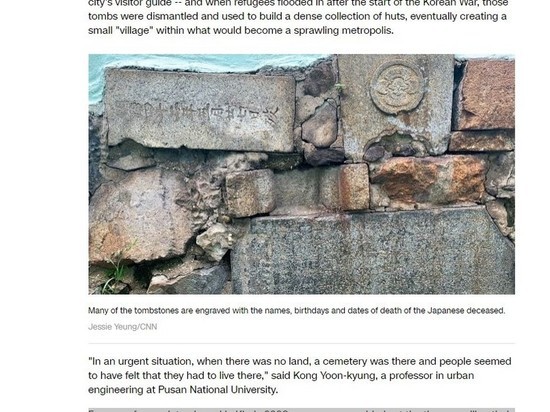

But upon closer inspection, visitors may notice an unusual building material embedded in the foundations of the houses, walls and steep stairs: tombstones inscribed with Japanese characters.

Ami-dong, also called Tombstone Village, was built at the height of the Korean War, which broke out in 1950 after North Korea invaded the South.

The conflict has displaced vast numbers of people across the Korean Peninsula, including an estimated over 640,000 North Koreans who have crossed the 38th parallel separating the two countries.

Inside South Korea, many citizens also fled to the south of the country, away from Seoul and the front line.

Many of these refugees made their way to Busan on South Korea’s southeast coast, one of only two cities never captured by North Korea during the war, the other being Daegu, 88 kilometers (55 miles) away.

Busan became the temporary wartime capital and UN forces built a perimeter around the city. Its relative safety – and its reputation – has made Busan “a massive refugee city and the last stronghold of national power,” according to the city’s official website.

But the newcomers faced a problem: finding accommodation. Space and resources were scarce as Busan was overpopulated.

Some found shelter in Ami-dong, a crematorium and cemetery located at the foot of the hilly mountains of Busan, built during the Japanese occupation of Korea from 1910 to 1945. The period of colonial rule and the use of sex slaves by Japan in wartime brothels. — this is one of the main historical factors that still underlie the bitter relations between the two countries .

According to an article in the city government’s official guidebook, during this colonial period, Busan’s habitable plains and central areas near the seaports were turned into Japanese territory. Meanwhile, poorer workers settled further inland, in the mountains where the ashes of the dead Japanese were once kept at the Ami-dong cemetery.

The tombstones were engraved with the names, birthdays, and death dates of the deceased in kanji, hiragana, katakana, and other forms of Japanese writing.

But the cemetery area was abandoned after the Japanese occupation ended, and when refugees poured in after the start of the Korean War, these graves were dismantled and used to build dense huts, eventually forming a small “village” inside what would become an expanding metropolis. .

Former refugees interviewed in Kim’s 2008 newspaper (many older people at the time recalled their childhood memories in Ami-dong) described demolishing cemetery walls and taking tombstones for use in construction, often throwing out the ashes in the process. According to Kim, the area became a center of community and survival as refugees tried to support their families by selling goods and services in Busan’s markets.

“Ami-dong was the boundary between life and death for the Japanese, the boundary between rural and urban areas for migrants, and the boundary between hometown and foreign place for refugees,” says one article about the unique village.

[ad_2]

Source link