“Komsomol Mafia”: a hundred years ago Vladimir Semichastny was born, who could change the fate of Russia

[ad_1]

Chairman of the KGB

Gifted with a bright political temperament and absolutely fearless, Vladimir Semichastny was born for politics. The main career ladder was the Komsomol, and he rapidly rose in position. He was only twenty-three years old when the then leader of Soviet Ukraine, Lazar Kaganovich, made him the leader of the Republican Komsomol. Ten years later, Nikita Khrushchev put him at the head of the All-Union Komsomol.

At the Komsomol Central Committee, Vladimir Semichastny became friends with another major figure in Russian history – Alexander Shelepin, who would become a member of the Politburo and secretary of the CPSU Central Committee. A powerful political tandem was formed.

At thirty-five, Semichastny headed the department of party bodies of the Central Committee for the Union Republics, that is, he became the chief personnel officer and zealously got down to business. He wanted not only to establish himself in a new role, but also to seriously shake up the secretarial corps.

The Secretary of the Central Committee for Ideology Mikhail Suslov was extremely dissatisfied:

—You just arrived and are already dispersing old footage?

Experienced apparatchiks found an opportunity to get rid of Semichastny: they sent him to Azerbaijan as the second secretary of the republican Central Committee.

“Vladimir Efimovich was remembered by the Central Committee apparatus for his independence of judgment, which he emphasized demonstratively,” recalled Mikhail Nazarov, who worked for many years in the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Azerbaijan. — Let’s say, after discussing some overly debatable issue, the result, as usual, is summed up by the First — V.Yu. Akhundov. After which the decision is put to a vote and adopted by a simple majority.

Semichastny more than once turned to stenographers in such cases:

– The question is accepted, but please write down my dissenting opinion…

The First and Second Secretaries usually had the same privileges. However, in all matters, the opinion and voice of the First were decisive… The significance of the Second was that it seemed to represent a kind of second center of power, limiting to a certain extent the omnipotence of the First.”

“I established such a procedure,” Semichastny recalled, “not a single decision of the Party Central Committee was issued without my visa.” Even if the head of the republic has already signed it.

But he did not stay in Baku. Khrushchev returned him to Moscow. At thirty-seven years old, he became chairman of the State Security Committee.

Shadow cabinet?

Shelepin and Semichastny actively participated in the removal of Khrushchev in October 1964. Without the KGB chairman, an attack against the owner of the country was in principle impossible.

Just in August 1991, a film was shown on television in which the former KGB chairman Semichastny told how Khrushchev was deprived of the post of First Secretary of the Party Central Committee and Chairman of the Council of Ministers. When the State Emergency Committee arose in those August days, Semichastny’s acquaintances joked: yes, it was you who explained to them how to act. But the then KGB chairman was nothing like Semichastny. Vladimir Efimovich had no shortage of will and determination.

Many then believed that Brezhnev was a temporary, weak figure. But the country needs a strong hand, so Brezhnev and his entourage will have to give way to Shelepin and Semichastny. They are younger, more energetic. A whole generation of young party workers who went through the Komsomol school was guided by them. These conversations reached Brezhnev. Leonid Ilyich probably had an unpleasant thought: what if Shelepin and Semichastny wanted to remove the new first secretary, just as they removed Khrushchev?

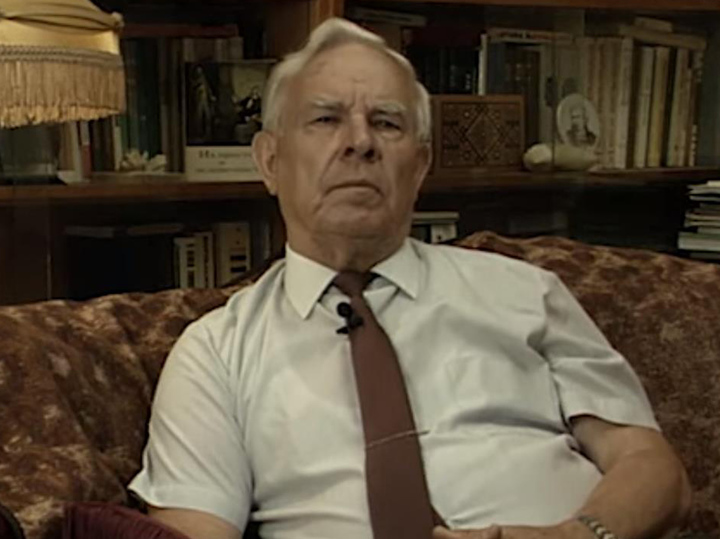

I met Semichastny when I came with a film crew to Vladimir Efimovich, already a pensioner, in his apartment on Patriarch’s Ponds. At first he was somewhat wary, then he began to talk lively and interestingly. He was not afraid of any questions and never found it difficult to answer. While he was alive, we often talked.

I asked Vladimir Efimovich:

— It is generally accepted that you intended to take all power in the country. It’s right?

— Shelepin and I were very close. At first he was the chairman of the KGB, then I became. And whoever is in the KGB, they have power in their hands, they can do anything… Brezhnev’s entourage tried to fuel this attitude. Brezhnev fell for this too.

They accused us of creating a shadow cabinet and installing our own personnel everywhere… Nonsense. We couldn’t do it! Next to Mikoyan, Suslov and others, we were Komsomol members in short pants. Then all the former Komsomol members were sent somewhere. The KGB was cleared of everyone we took from the Komsomol. This is proof that Brezhnev was afraid of us. Our cadres were younger and more agile. Solzhenitsyn said about Shelepin that he was made of iron. Nonsense.

Khrushchev needed a structure that would know exactly what was happening in the country and punish deceivers. He made Shelepin Secretary of the Central Committee, Deputy Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the USSR, and in November 1962 appointed Chairman of the Committee of Party and State Control. This set of positions made Shelepin one of the most influential people in the country.

Semichastny:

— Shelepin had the right to punish and punish both on the party line and on the Soviet one. Party control has become more terrible than any body. Even worse than the KGB. State party control has gained strength. This also added to Shelepin that he was made of iron. No, he is a good, gentle person. I knew Shelepin very well. He is a person of high organization and responsibility. He hated disorganization; he worked on his own speeches and did not chew other people’s gum.

Arriving at the KGB, he sharply reduced the apparatus. I continued. We set the task: the main thing for the KGB is prevention, prevention, education. No need to plant. In my time and in Shelepin’s time, the fewest people were imprisoned for ideological crimes. We handled the personnel very carefully and carefully. It’s not in our spirit to come and disperse. We replenished our staff with young people when it was really necessary.

— Why did Brezhnev remove you from the State Security Committee in May 1967?

Semichastny:

— Khrushchev’s departure began to be called a coup. But this is not a revolution, I disagree! Khrushchev’s resignation passed quietly, the KGB carried out everything perfectly. In the feature film “Grey Wolves” eight corpses are shown. This is wrong! There wasn’t a scratch! There was no need. This is how they treated Khrushchev brilliantly. And this alarmed Brezhnev… When Khrushchev was removed, Brezhnev immediately began to think that he needed his own man in the KGB. This is the fate of anyone associated with the “displacement”: do your job and get out, because you know a lot. The leader who was nominated is obliged to him, but he does not want to be obliged at all…

Just six months after Brezhnev arrived, he was looking for his figure in the KGB. He calls me: isn’t it time for you, Volodya, to join our cohort? I’m taking my time, I understand what it’s about. Brezhnev: maybe that’s enough in the committee? You will come to us. I say: no, it’s too early. Brezhnev: oh well… I didn’t return to this again. I understood: there is a question, and it is maturing in the head of the Secretary General.

Link to Ukraine

Stalin’s daughter Svetlana Alliluyeva married the Indian communist Raja Brij Singh. In Moscow he worked at the Foreign Literature publishing house. Her fourth husband turned out to be a sick man. And soon he died in her arms. He bequeathed to bury him in his homeland.

With the permission of the head of government Alexei Kosygin, Svetlana was released to India. On March 7, 1967, when Moscow was preparing to adequately celebrate International Women’s Solidarity Day, Stalin’s daughter came to the American embassy in Delhi and asked for political asylum. She was immediately taken to Italy, then to Switzerland, and from there she was taken to the United States.

The flight of Svetlana Alliluyeva turned out to be a convenient reason to get rid of the person whom Brezhnev did not want to see next to him. On May 19, 1967, at a meeting of the Politburo, Semichastny was removed from the post of KGB chairman and appointed first deputy chairman of the Council of Ministers of Ukraine.

Semichastny’s political career ended when he was only forty-three years old. Others at this age still stand at the foot of Olympus and look up in fascination. He did not believe that it was all over and there was no turning back. But he was sent to Kyiv, and the path to Moscow was closed to him. In the government of Ukraine, Vladimir Efimovich dealt with issues of culture and sports.

The then leader of Soviet Ukraine, Pyotr Shelest, recalled:

“He was oppressed, bitter, at the mention of Brezhnev’s name it seemed as if a high voltage current was passing through his body, and it is not difficult to imagine what Semichastny could have done with Brezhnev if he had had such an opportunity…

Semichastny worked in Ukraine for fourteen years. He asked many times to find another job for him. But he was allowed to return to Moscow only a year before Brezhnev’s death. We found a position in the Knowledge Society.

Last question

The further the Brezhnev era goes, the more it is perceived as a symbol of lost peace and reliability, stability and justice. But then the most primitive answers were given to all the acute, painful and urgent questions. And a frightened call sounded: don’t change anything! Leave it as is!

If humanity had always been guided by such principles, then people would still be living in caves to this day. It is no coincidence that at the end of the Soviet era there was a feeling of decline…

Shelepin, Semichastny and their Komsomol comrades said that Brezhnev and his team threw out of politics an entire generation, young and educated, who wanted change and were capable of it. That is why the Brezhnev years became a time of missed opportunities and wasted energy.

The young, educated part of the apparatus assumed that the economy needed reforms, primarily technical modernization. She wanted economic reforms along with a rigid ideological line. This is approximately the path that China chose under Deng Xiaoping. If Shelepin and Semichastny had led the country, their friends said, our country would have followed, relatively speaking, the Chinese path.

It is generally accepted that history does not know the subjunctive mood. Why exactly? If you look into the past, historical forks are obvious, when different paths opened up for the country. The story is multivariate.

Semichastny:

“We followed an unbeaten path, we stumbled somewhere, we made mistakes.” We walked straight and sometimes broke wood, entire forests flew and were destroyed. What was needed was a sober adjustment, but not a breakdown. Don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater. We couldn’t lose everything we’d achieved.

Vladimir Efimovich Semichastny died on January 12, 2001. He was three days short of his 77th birthday.

In those years, every evening in the main newscast of our television company I made a commentary on the main event of the day. The topic of the commentary that evening had already been decided, and I drafted the text. I never used a teleprompter, but I put the text in front of me – just in case…

I learned about Semichastny’s death fifteen minutes before the broadcast. I threw the finished text into the trash. While walking to the studio, I decided that I simply had to say the last word about Semichastny and about that era in general…

There are two questions that historians have been looking for answers to for many years. First: why did the Komsomol lose? Second: what would happen to the country if they won the power struggle? The first question is easier to answer. But the second one is more important.

“What would Russia be like,” I asked Semichastny, “if you and Shelepin had managed to realize yourselves to the fullest?”

Vladimir Efimovich answered without hesitation:

— All paths of development and growth and advancement would be different. And most importantly: the USSR would survive.

[ad_2]

Source link