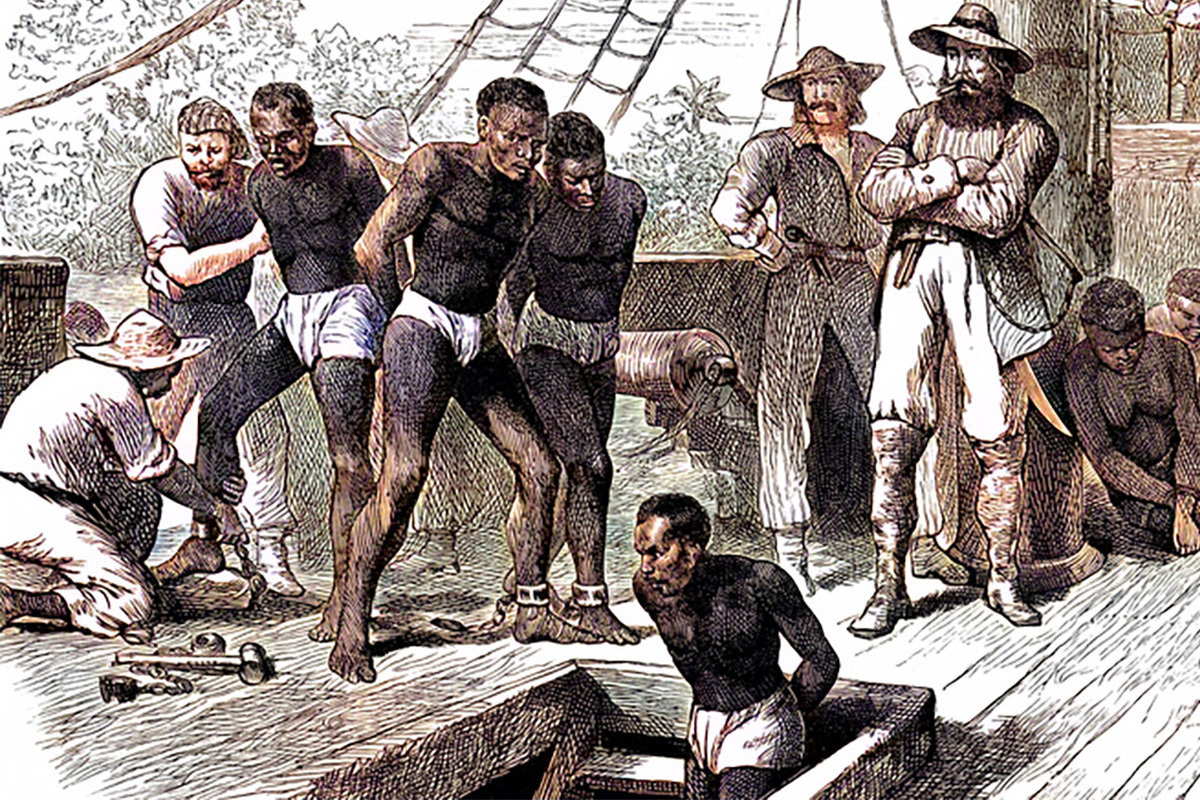

Historians have revealed shocking facts about the slave trade in the enlightened West

[ad_1]

Transatlantic slavery in the West continued for many years after 1867, says British historian Hannah Durkin. The evidence she uncovered included ships carrying “live goods” arriving in Cuba in 1872 and people captured in Benin in 1873;

Historians typically assume that the transatlantic slave trade in the West ended in 1867, but new research suggests it actually continued into the next decade.

As The Guardian exclusively writes, Dr Hannah Durkin, a historian and former lecturer at Newcastle University, has unearthed evidence that two slave ships arrived in Cuba in 1872. One ship, sailing under the Portuguese flag, carried 200 prisoners ranging in age from 10 to 40 years, and the second was believed to be an American ship with 630 prisoners in its hold.

Durkin said she found references to the arrivals of these ships in American newspapers that year. “It shows how recently the slave trade ended. The thefts of human lives were erased from history and were not recorded,” notes the historian.

Other newly discovered evidence includes Hansard’s parliamentary report from 1872, in which a British politician disputes “the assurances of the Spanish Government that no slaves have been imported into Cuba in recent years.”

Durkin says that although Spain officially ended its slave trade in 1867, it came across the report of explorer Sir Henry Morton Stanley, who traveled through Benin and visited the slave port of Ouidah in 1873. He wrote about seeing 300 people locked in a barracoon, a slave pen, and noted that two slave ships had recently sailed from that port.

According to Durkin, Ouidah was the second most important slave port in all of Africa, second only to Luanda in Angola. “This region received the European nickname ‘Slave Coast’ due to the huge number of people who were forcibly removed from there between the mid-17th and mid-19th centuries. It is estimated that nearly 2 million people, approximately one in six of all enslaved people sent to America, were transported from the Bight of Benin.”

Although Stanley’s report appeared in the New York Herald at the time, Durkin notes that it was another overlooked key piece of evidence that she unearthed. There have been rumors of a later trade, but this evidence supports the findings of Cuban historians that human trafficking continued into the 1870s.

Newly digitized 19th-century newspapers were particularly revealing, she said: “Historians have previously had a hard time accessing these sources, which is one of the reasons I was able to find so many.”

The research will be featured in her upcoming book, Survivors: The Lost Stories of the Last Captives of the Atlantic Slave Trade. Drawing on never-before-seen archival material, it tells the story of the Clotilda, the last American ship of the Atlantic slave trade.

She identified for the first time most of the 110 slaves of the Clotilda and tracked down their descendants. One of them had a previously unpublished 1984 interview with Amy Greenwood Phillips’ grandson that her family had preserved. She was a teenager when she was enslaved and sent to work on a plantation in Alabama.

Durkin says “Amy’s enslaver was a man named Greenwood. According to her grandson Percy Philip Marino, Amy’s enslaver was a “good man” but he turned Amy over to unknown enslavers in another state who beat her. He took Amy in when he learned of the abuse, but the scars on her legs never healed.”

Others told Durkin about the sexual abuse their ancestors suffered. She found a story about a woman who was enslaved at the age of 13. The horrors she endured included being forced to sleep with African Americans and Native Americans so she could have children who could also be enslaved.

Durkin says: “There is a lot of evidence of a system in which enslavers wanted to produce young enslaved children because it would make them richer. Whether it was the sugar plantations of Cuba or the cotton plantations of the southern United States, wherever slavery existed, it was a barbaric system that completely dehumanized people.”

Durkin’s research found that almost all of the Clotilde survivors were Yoruba speakers from the same town in present-day southwestern Nigeria, casting doubt on previous findings that they were from different locations in Benin and Nigeria.

[ad_2]

Source link