Declassified spy photos helped archaeologists solve ancient Roman mysteries

[ad_1]

Declassified photographs taken by US spy satellites launched during the Cold War have revealed an archaeological sensation. Unknown Roman-era forts have been discovered in what is now Iraq and Syria. “This has dramatic consequences for our understanding,” the experts said.

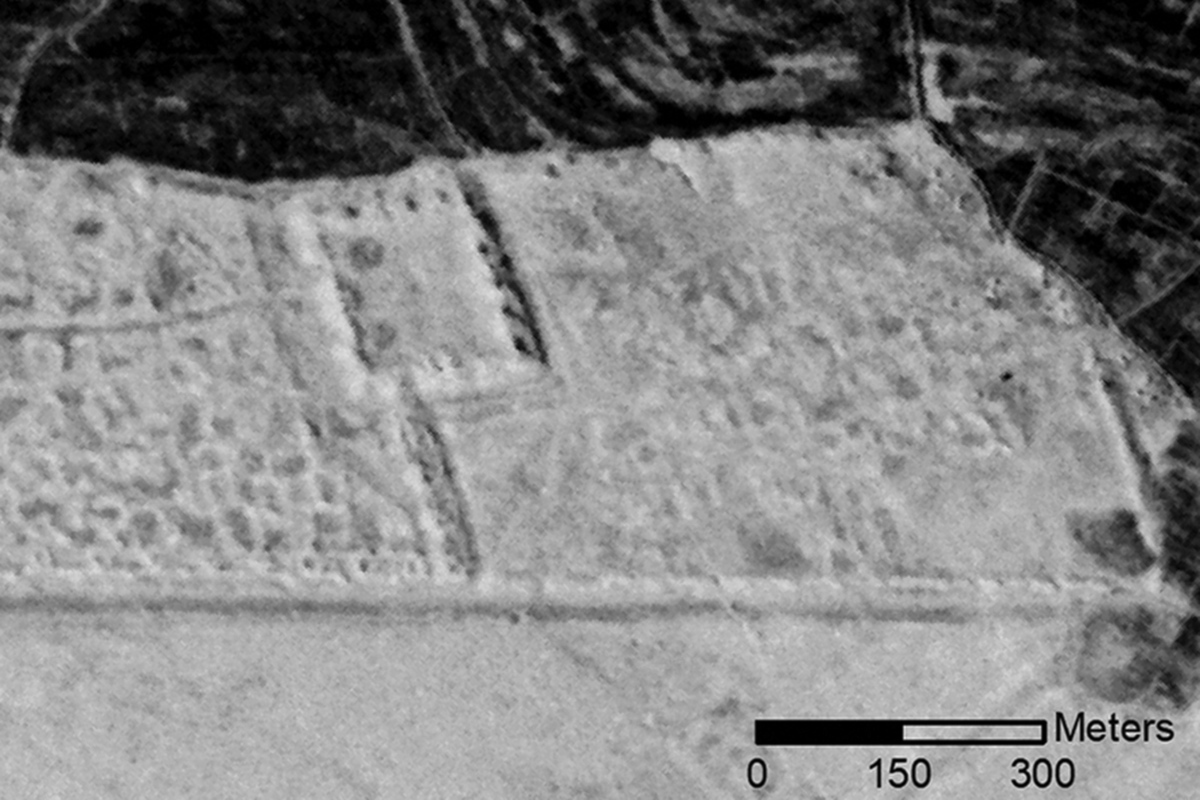

Archaeologists studying aerial photographs taken in the 1960s and 1970s say they have discovered 396 unknown Roman forts in Syria and Iraq, The Guardian reports. These satellite photographs give archaeologists unique insight into what the region’s terrain once looked like. Traces of Roman forts in many places that are visible in photographs have disappeared in modern times due to the rapid growth of cities and the construction of reservoirs.

The results, published Oct. 26 in the international academic journal of archeology Antiquity, have led scientists to reassess the life of the Romans. The discovery suggests that the ancient border between the Roman Empire and their neighbors to the east was a place of cultural exchange rather than constant warfare.

The images studied were part of the world’s first spy satellite program, conducted during the geopolitical tensions – the Cold War – between the United States and the Soviet Union and their allies, the Western and Eastern blocs.

CORONA and HEXAGON satellite photographs show that forts were used for a variety of purposes, including facilitating caravan trade, troop movements, and communications throughout the region to facilitate communication between east and west, rather than simply serving as a means of defense. The Corona images were declassified in 1995, and the Hexagon photographs were made public in 2011.

A previous survey of the region in 1934 by Antoine Poidebard, a French Jesuit explorer who used a biplane, recorded a line of 116 forts.

Until now, historians have assumed that these structures were part of a defensive line against Arab and Persian invasions, as well as against nomadic marauding tribes who loved to take captives and attack slaves.

The authors say the question now becomes: “Was it a wall or a road?”

“Since the 1930s, historians and archaeologists have debated the strategic or political purpose of this fortification system. However, few scholars have questioned Poidebard’s basic observation that there was a line of forts defining Rome’s eastern border,” said the study’s lead author, Professor Jesse Casana.

Some of the newly discovered sites have been earmarked for future on-site archaeological research, but others are in active military zones that are off-limits to researchers.

Significantly, the discovery indicates that the boundaries of the Roman world were less rigidly defined and isolated than previously thought, the authors say.

The Romans were a military society, but they clearly valued trade and connections with regions not under their direct control, they added. Rather than presenting an impenetrable wall, they provided oases of security and order along well-travelled Roman roads.

According to Kazan, borders in this world “were places of dynamic cultural exchange and the movement of goods and ideas” rather than barriers. And perhaps that perspective holds a lesson for the modern era, he added.

“Historically, as an archaeologist, I can say that ancient states tried to build walls across borders, and it was a universal failure. If archeology somehow contributes to modern discourse, I hope that building giant walls to keep people out is a bad plan,” said Professor Casana.

Archaeologist Rocco Palermo of Bryn Morpris College told The National Geographic that this type of imagery has become a vital resource for explorers, and studying it in detail is a crucial achievement.

Satellite photographs are invaluable to archaeologists because they preserve images of landscapes: “Agriculture and urbanization have destroyed many archaeological sites and sites. These old images allow us to see things that are often either hidden or no longer exist today,” Casana admitted in an interview with CNN.

According to him, the images concealed value for the archaeological record: “We were able to confidently identify the surviving archaeological remains of only 38 of the 116 forts of Poidebard. “In addition, many of the probable Roman forts we document in this study have already been destroyed by recent urban or agricultural development, and countless others are under serious threat.”

As more images, such as those of the U2 spy plane, are declassified, many new archaeological discoveries can be made. Professor Casana noted that “careful analysis of these important data holds enormous potential for future discoveries in the Middle East and beyond.”

[ad_2]

Source link