The communist almost reached the Constitutional Court – Newspaper Kommersant No. 181 (7382) of 09/30/2022

[ad_1]

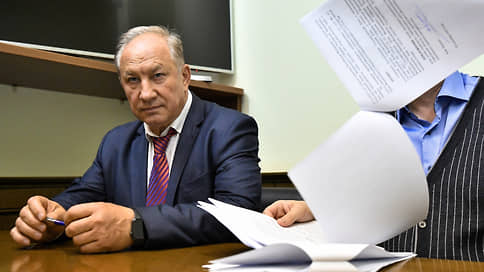

The Supreme Court (SC) on Thursday rejected the complaint of the representative of the Communist Party Valery Rashkin to deprive him of his status as a State Duma deputy for illegal hunting. The motivational part will become known later, but for now it has only been announced that the court did not take the side of the communist. Mr. Rashkin himself is not surprised by the refusal and plans to go to the Constitutional Court (CC) in order to challenge the right of the State Duma to deprive deputies of the powers received from the people.

“To refuse to satisfy the claims,” Judge Vyacheslav Kirillov announced the operative part of the decision of the Supreme Court regarding the complaint of Valery Rashkin. The ex-deputy tried to prove that the State Duma had deprived him of his powers in violation of the regulations: at the time of this decision, on May 25, the chamber had not yet received certified documents from the court of first instance. The latter could provide a copy of the verdict only after he himself received the case from the appeal, and this happened only on May 30. In addition, Valery Rashkin complained, the credentials committee, which initiated the issue of depriving the deputy of his powers, did not hold a face-to-face meeting on this matter. The ex-deputy also believes that he has discovered a significant gap in the legislation in the very mechanism for depriving a parliamentarian of powers: the people endow the deputy with the latter, which means that his parliamentary colleagues simply cannot select them. Mr. Rashkin appealed to the decision of the Constitutional Court of April 12, 1995 on the case on the interpretation of a number of articles of the Constitution. It notes that acts of parliament should embody the interests of the majority in society, and not just the parliamentary majority. The decision adopted by the State Duma, according to the communist, was of a pronounced political nature: 337 out of 450 deputies voted for it, 301 of which represent the United Russia faction. The communist called this decision “political reprisal against an opposition deputy.” Kirill Serdyukov, Mr. Rashkin’s lawyer, in turn, reminded the court that deprivation of the right to hold a certain position is a form of criminal punishment. But the Kalininsky District Court, which sentenced the ex-deputy, did not impose such sanctions.

State Duma deputy Sergei Obukhov, who spoke at the trial in support of his party colleague, said that he was embarrassed by the speed of the decision regarding Valery Rashkin. Mr. Obukhov suggested to his parliamentary colleagues not to rush and wait for all the documents to arrive, but he was not supported.

The representative of the State Duma asked the court to consider the case in his absence. The written explanations say that the decision to deprive Deputy Rashkin of his powers was made in full accordance with the law and the regulations of the State Duma. The Kalininsky District Court, as expected, within three days informed the State Duma that the verdict against the deputy had entered into force and provided copies. And the regulations of the State Duma establish only a quorum for the credentials committee, but not a ban on voting by poll. Thus, the applicant’s arguments are refuted by the evidence and have no legal value, the explanation stated.

Mr. Rashkin was not surprised by the decision of the Supreme Court and told Kommersant that now he would have a basis for applying to the Constitutional Court.

Earlier, the latter had already rejected the communist’s appeal due to the lack of a specific court case: the ex-deputy appealed to the highest court without exhausting all remedies, the secretariat of the Constitutional Court explained at the time.

Now Valery Rashkin again intends to draw the attention of the Constitutional Court to the obvious gaps in the mechanism for depriving a deputy of his powers, given that recently the number of grounds for such a decision has increased dramatically: a deputy can be “dismissed” even for absenteeism at meetings. The former parliamentarian fears that the position in which the constitutional majority in the State Duma belongs to opponents of the Communist Party opens a direct path to political reprisal. The communist believes that only a court can make such decisions.

Most likely, the Constitutional Court will not consider Rashkin’s complaint this time either, and will write in a refusal ruling that a person who claims public status should enjoy special confidence, predicts lawyer Alexei Rybin.

Until now, he recalls, this is the argument the court has used when rejecting complaints about restrictions on passive suffrage, for example, in connection with involvement in the activities of terrorist or extremist organizations. Meanwhile, there is clearly a reason in the deputy’s arguments, the lawyer believes, the norm is formulated very harshly and allows depriving a deputy of his status under almost any pretext, especially taking into account modern political realities.

[ad_2]

Source link