Business schemes cut in the war: how they profited in World War I

[ad_1]

We have experienced this many times in our lives. When we were deceived by our former partners, this is at least understandable. But when we were promised two cars for a voucher, or in the midst of perestroika, they convinced us that the market and the planned economy were incompatible, and at the same time gave a deadly argument: “You can’t be a little pregnant!” – it was either mean or demonstrated the stupidity of our elite. At the same time, they urged and said: “You can’t jump over the abyss in two times,” not letting you think that it might be better to build a bridge.

I understand that the initiators of the transformations thought to themselves: “Saw, Shura, she is golden.” And judging by the results, yes.

Until now, many key decisions are made by effective managers.

And today I want to talk about two related human feelings – greed and stupidity.

Once in a documentary, I was struck by an episode in which a shark with an open belly on the deck of a fishing ship tried to swallow a smaller fish lying nearby. In the same way, Western speculators, ignoring the rules adopted throughout the world for making and adjusting portfolio decisions, in 1998, having already made more than good money on our GKOs, continued to hope for fabulous future profits – the growing yield on government securities did not let them “eat up”. And got a lesson in financial literacy.

Today, everyone is outraged by the actions of hucksters who make money by inflating prices for the most necessary goods needed by mobilized compatriots. They operate on the principle of “sell to a neighbor whose house burned down, building materials are more expensive.”

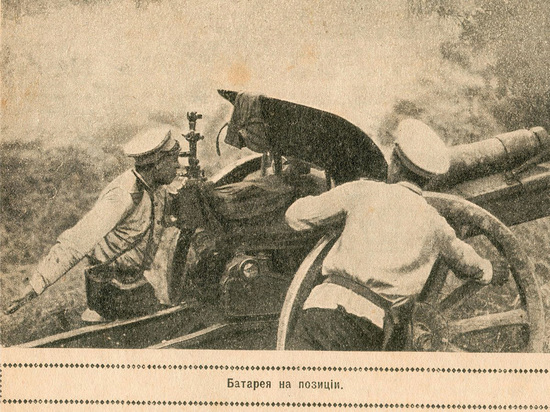

I would suggest looking for analogies at the beginning of the 20th century. And as a witness, I will take General Alexei Manikovsky. In 1915, he headed the Main Artillery Directorate and immediately announced the shameless robbery of the treasury.

The First World War was on. The French Minister Albert Thomas, who arrived in Russia in the spring of 1916, described the mood as follows: “There is a powerful liberal movement in Moscow. Most of those who adhere to it will patiently wait for victory in order to present their demands, but some are more patient, while others base their calculations on defeat and think that this is the surer way for the triumph of their political views.

Private factories, especially in metallurgy, inflated prices (I will say right away – not as much as modern entrepreneurs). Hope remained only in the state-owned industry. In 1916, the state-owned Tula plant supplied a machine gun along with two spare barrels for 1370 rubles each, while private entrepreneurs offered the same machine gun twice as expensive. At the same time, they also demanded that they be provided with spare barrels, semi-finished products and all kinds of benefits. Entrepreneurs negotiated contracts for the supply of a 3-inch gun from 10.6 to 12 thousand rubles per gun, while the state-owned Petrograd and Perm plants supplied them at a price of 5 to 6 thousand rubles per barrel. The price of the Putilov plant – one of the most powerful in the country – was intermediate, 9 thousand rubles. True, he did not fulfill the order very successfully, out of the 8647 guns ordered by the GAU already during the war, by September 1, 1915, he delivered only 88, that is, a little more than 1%. A similar picture was with the contract for the production of 6-inch howitzer bombs. The plant doubled the prices, and when it signed the contract, it began, under various pretexts, to demand new benefits, reduce the volume of orders and increase the timing of their implementation. And in the end, the program failed – until January 1916, he did not hand over a single 6-inch projectile to the customer.

At the same time, the owner of the Putilov plant, Putilov, successfully used the following business scheme: he took 40 million rubles in advance from the treasury to fulfill an order, another 11 million from the State Bank on preferential terms, he contributed funds to his Russian-Asian Bank, which took extortionate money from customers ( at that time) interest – from 10 to 16 per annum. That is, accepting significant advances with one hand as a breeder, appropriated them with the other hand as a banker. Nothing personal, just business!

At the same time, the Council of Congresses of the Metalworking Industry categorically protested against the expansion of the state sector of the economy, arguing, referring to the European experience, that it was inefficient. And this at a time when state-owned arsenals were being built in England and factories that produced shells were nationalized in large numbers.

I will touch separately on the situation with the production of explosives. The Russian chemical industry, like most other industries, was oriented towards foreign suppliers and, after the outbreak of the war, was unable to meet the needs of the military department. Nothing was done to improve the situation in the first months of the war. Many then believed that the war would be short and everything would return to established practice.

And only in the most difficult situation of the summer of 1915 was the right choice made in favor of creating our own production facilities. Under these conditions, it took an average of one year to build one chemical plant. And from January 1916 to May 1917, 33 sulfuric acid plants were put into operation. Plants for the production of ammonium nitrate were built just as quickly.

As a result, only from February to October 1915, the productivity of state-owned factories that produced explosives more than doubled. And here we must pay tribute to entrepreneurs – their volumes have grown more than 50 times. They can if they want! But again, an ambush: until June 1, 1916, contractors – enterprises from Yekaterinoslav, Kyiv, Odessa, Kharkov, Kherson (what familiar names are now) – were supposed to supply 743 thousand pounds of bar iron, but less than 1% of the order was completed a month before the deadline .

In addition, Alexei Manikovsky was then outraged by the huge number of swindlers revolving around his GAU. To resolve their issues, they even got to the front, presenting business cards of some members of the State Duma.

In 1915, a powerful public organization of entrepreneurs appeared in Russia – the Central Military Industrial Committee, “the trade union of Russian oligarchs.” Something like our RSPP. It was headed by the “Russian Lloyd George”, a major banker and industrialist, former chairman of the State Duma, a prominent liberal (in 1917 he headed the Liberal Republican Party of Russia, not at all the Liberal Democratic Party) Alexander Guchkov. The Committee placed orders with its factories, received from them 1% of the contract value and, naturally, was interested in raising prices.

And it would be fine if the committee clearly carried out the work it had undertaken, but in the first six months of its existence it did this by no more than 2–3%, and for the entire 1916 military orders in the amount of 280 million rubles were executed by the committees on time no more than on 10%.

The Putilov plant, by the way, started working at full capacity only after it was taken into state custody with the complete replacement of the old plant management with government-appointed specialists. Manikovsky said about this: “Not a bad plant, but, unfortunately, it is in the tenacious hands of bankers. Bankers think about profits, not about protecting the Motherland. They trade too much. They have a balance, an asset-liability, various considerations, and we are military people, we are not up to this now.

The fate of most of the bright entrepreneurs of that time is sad.

“Russian Morgan” Nikolai Vtorov was shot dead in his office in Moscow in May 1918 under unclear circumstances.

The representative of one of the most famous families of industrialists and entrepreneurs in Russia, Pavel Ryabushinsky, died in France from tuberculosis. He was 53 years old. A few years later, the Great Depression and the thoughtless greed of one of the brothers led the mighty clan to complete ruin. In 1942, the widow of Stepan Ryabushinsky had to sell the last things in order to adequately bury the once richest man in Tsarist Russia.

The bread merchant Nikolai Stakheev (the prototype of Ippolit Matveyevich Vorobyaninov) exchanged his wealth for the opportunity to leave the country.

Finally, Alexei Putilov died in the late 1930s in France. All his movable and immovable property in Russia was immediately confiscated by a special decree of the Council of People’s Commissars. The wife, daughter and son managed to get to France – they fled from Soviet Russia across the ice of the Gulf of Finland.

Shouldn’t our businessmen, who made a fortune on the destruction of automobile factories, now provide the army with off-road vehicles; those who have privatized factories for the production of night vision devices to start supplying imported analogues; who made money on the destruction of civil aviation – drones. But you never know in Russia and others who have become successful at the expense of us.

And I would advise officials who have gone too far from greed to read the story of Alexei Tolstoy “The Viper”. This story could easily become relevant!

[ad_2]

Source link