The descendants of Aivazovsky revealed the secrets of the artist: despot, bigamist, darling of fortune

[ad_1]

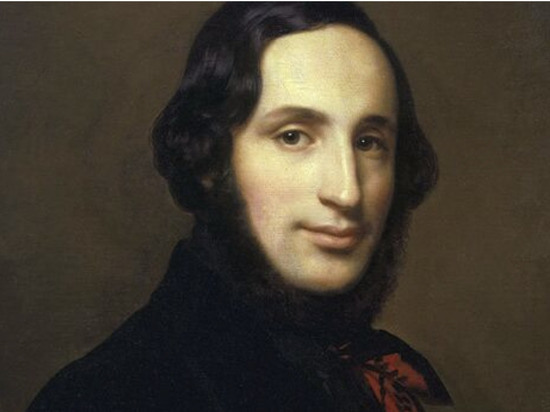

It would seem that so much has been written about Ivan Aivazovsky that there is nothing to add. However, reading the recently published book “Aivazovsky and his descendants: from the surviving archives”, it turns out that this is only an appearance. On the surface is a brilliant creative biography of the master, the character and versatile activities of Ivan Konstantinovich are described in strokes, through whose efforts his native Feodosia flourished (water supply, a railway, a theater and a gallery appeared there through his efforts). Now, for the first time, readers have a chance to touch the genius of Aivazovsky through the home memories of his relatives, to witness the noisy balls on the artist’s estates and eyewitnesses of events centered on the personalities of emperors, mayors, ministers, poets, writers, and artists. Aivazovsky, for all his breadth of soul and energy, was not easy. His determined nature once nearly led him to exile in Siberia, his grandson claims.

This 330-page edition was in preparation for several years, but active work on it happened only in March 2022. At that turning point, Natalia Arendt, in whose veins the blood of the great marine painter flows, decided to complete the work she had begun – work on the book was completed quite recently. “History repeats itself even now, in the 21st century, exactly a century later, we are experiencing a historical turning point similar in tragedy (…) I felt that the time had come,” she writes in the introductory article, where she sketches the fate of her relatives. Most of them were forced to leave Russia after the 1917 revolution – many descendants, and with them the archives, and the legacy of the artist, now – in the UK, USA, Australia. Everyone has their own dramatic destiny, many inherited their grandfather’s talent and followed in his footsteps, others became writers, pilots, doctors…

Examining each branch of the branched Aivazovsky tree, we are presented with a large-scale portrait of the Russian intelligentsia. The book, which contains memoirs and unique photo archives, paintings and letters from the descendants of Ivan Aivazovsky, was made possible thanks to the art critic, collector, gallery owner, adviser to the director of the Museum of the Russian Diaspora, Lyubov Agafonova. Her article entitled “Crimean Shores” opens the publication and sets the horizon from which the reader looks at the stories told here. We look back at the pictures of the past from the steep Crimean coasts, “the land of graves, prayers and meditations,” as Maximilian Voloshin wrote, and where “epochs, cultures and natural elements, far from each other, mysteriously intertwined,” Agafonova adds.

The first part of the book contains texts and poems by Alexander Aivazovsky (Latry), the artist’s grandson, who remembered his grandfather well and himself became a participant in many historical events. He was born in 1883 in the Crimea, and died in 1956 in New York. At the beginning, he sets out the biography of Ivan Konstantinovich in his own way, noting all the important, well-known milestones and stages. With some facts experts can argue. For example, Alexandra Aivazovsky writes that a creative dynasty comes from Aivaz Pasha, the commandant of a Turkish fortress, who was killed in the 18th century during the Russian-Turkish war. However, the officially accepted version says that Hovhannes Ayvazyan (aka Ivan Aivazovsky) was born in the family of an Armenian merchant Gevorg (Konstantin), who moved to Feodosia from Poland. There is another point of discussion in the presentation of the fate of the artist. At the beginning of 1835, by order of the Academy of Arts, Aivazovsky was appointed assistant to the famous French marine painter Philip Tanner, who arrived in St. Petersburg at the invitation of the imperial court. But instead of teaching the young man, the Frenchman used him as a servant and forbade him to write independent works. The young man was only allowed to clean the palettes and make auxiliary sketches for the teacher’s paintings. But one day the student plucked up courage, wrote his own work and showed it at the exhibition, secretly from the mentor. Tanner was beside himself with rage, a serious scandal erupted. The work was removed from the review at the insistence of the French marine painter. But thanks to this incident, Emperor Nicholas I himself drew attention to the young artist, the sovereign bought Aivazovsky’s scandalous marina, and continued to support him, followed his fate, as a result, they became good friends. Since then, fortune has not changed the artist.

So, according to the grandson of the artist Aivazovsky, it was none other than the famous master Alexander Orlovsky who pushed Ivan to take a decisive step. He writes that two artists, young and honored, collided in an art store, where they got into a conversation. Orlovsky told Aivazovsky: “Write and exhibit. No one can stop you…” Other biographies also describe this episode, a turning point for a young man brought up in strict Armenian traditions. Only in the place of Orlovsky is the historian and draftsman Alexei Olenin (according to the book of the Crimean historian Yevgeny Belousov). As it was in fact, we are unlikely to find out, the exact data on this episode can no longer be found today. However, these are details that do not violate the general thread of the narrative and are more noticeable to specialists. It is worth noting that all texts are read easily – in one breath. The most interesting begins after the retelling of a well-known biography, seasoned with curious details. Reading living memories, we seem to be transported to visit the artist.

Alexander Aivazovsky first met his grandfather when he was 9 years old. And all because once Ivan Konstantinovich, already in his years and having four daughters from the beautiful Scottish Julia Grevs, suddenly decided to get married. Once he stopped by his daughter Elena in Yalta (Alexander’s mother), with his usual vigor ordered to urgently build shops, promised to send money and drove off to one of his estates – Sheikh-Mamai. But instead of financial support, the daughter, after some time, unexpectedly received an invitation to the wedding from her father. It turned out that Aivazovsky, passing through the German colony, fell in love with the daughter of a shopkeeper, Armenian Anna Burnazyan-Sarkizova. And he decided to get married immediately. According to the grandson, he did not bother to ask for a divorce. Everyone turned a blind eye to the bigamy of the honored master, until a friend of Yulia Grevs, General Admiral Strukov, reported to Alexander III himself that Aivazovsky had left his first wife without a livelihood. Then the emperor threatened Aivazovsky with exile to Siberia and deprivation of all special rights and privileges with which he was endowed. After that, Aivazovsky sent 60 thousand rubles to his first wife.

Note here that in other works the same story is told differently. Aivazovsky met young Anna not in the shop, the young woman followed the funeral procession and attracted his attention with her beauty. According to the Armenian Museum of Moscow and the culture of nations, the artist nevertheless asked for a divorce, linking his decision, in addition to the surging feelings, with the illness of his first wife: character” (from the petition for divorce). The artist provided for Julia, who lived in Odessa, sending her 500-600 rubles a month. The divorce petition filed by him was granted in 1877, and in 1882 the wedding took place. However, according to his grandson, Ivan Konstantinovich remained a bigamist.

However, after the death of Yulia Grevs, the family reconciled. From the age of 9, Alexander regularly visited his grandfather. His characterizations and sketches are quite captivating. “Kind by nature, he could be cruel at times. Always sincerely indignant at injustice, at the same time he himself could be deeply unjust. The grandson tells how the artist dressed brilliantly, with a needle, played vint with passion, controlled every little thing. Everyone had to gather for breakfast at exactly 8, and nothing else. Once, having met a beggar on the street, Aivazovsky scolded him for idleness, and immediately rewarded him with a land plot so that he could work and feed himself. He had such a temper.

The description of the death of the artist is indicative. He went to St. Petersburg to close his exhibition and did not want to extend the vernissage even for a day for Emperor Nicholas II, who did not have time to arrive at the opening time of the exhibition. No matter how they persuaded the 82-year-old artist, he began to pack the paintings. In the end, he agreed to move the work to the Winter Palace for three days, and the royal family had time to enjoy the master’s enchanting marinas. Returning from St. Petersburg to the Crimea, Aivazovsky managed to visit his Sheikh-Mamai estate to check how the swings were made for the children of employees, tried them out, went to Feodosia, played cards with friends in the evening, and died of a brain hemorrhage at night. The unfinished painting “Explosion of the Ship” remained in the workshop. Until his last breath, the artist remained true to himself – incredibly energetic, despite his age.

In addition to the biography of the grandfather-artist, Alexander Aivazovsky’s texts about Russian emperors are given. Among them, perhaps the most interesting concerns Alexander I. It turns out that the great-grandfather of the writer was a friend of the emperor. Yakov Grevs (father of Yulia, Aivazovsky’s first wife) often visited him, and on the day of the sovereign’s death he suddenly disappeared, leaving his family forever. Alexander, telling this story, suggests that it can serve as confirmation of the legend that the emperor did not actually die of illness in Taganrog, but staged his death…

The subsequent sections tell about the fate of the artist’s descendants, who led a comfortable life in tsarist Russia, and then scattered around the world in a whirlwind of revolutions and wars. For the first time in Russian, you can read the memoirs of Gayane Mikeladze, the great-granddaughter of the marine painter. Among other very intense and dramatic memories, she characterizes Uncle Alya (Alexander Aivazovsky). He was his mother’s favorite and lived in grand style in St. Petersburg, just like his grandfather. Only the family had to pay for his “breadth”, which caused him a lot of trouble for his relatives. Gayane retells a curious moment about him: “It so happened that Uncle Alexander was just on duty when Stalin first robbed the Tiflis bank.” Aivazovsky’s grandson pursued the future Secretary General on horseback, but did not catch up. And if he had overtaken the robber, the story would have gone in some other direction.

Such private stories concerning the global processes of Russian history fill this book and make it incredibly fascinating for any reader, even those who are not at all versed in art. Before us is not an art history work, but a personal history of the world …

[ad_2]

Source link