Vladimir Kekhman rewrote Dumas the son – MK

[ad_1]

Last weekend in St. Petersburg, at the Mikhailovsky Theater, the premiere of the opera “The Lady of the Camellias” took place, attention to which was riveted from the very moment the name of the stage director, Vladimir Kekhman, was announced. Mikhailovsky’s artistic director, better known as the manager of all Rus’, for the first time entered foreign territory – artistic territory. But it’s one thing to put together a concert (for example, for the 125th anniversary of the Moscow Art Theater), another thing is to offer an artistic solution to Verdi’s operatic masterpiece, known as La Traviata, which has had many interesting stage and film incarnations in its history. From the premiere show – MK columnist.

I don’t remember any theater allowing itself to decorate the hall with fresh flowers. But Mikhailovsky allowed it: a weighty-looking garland of roses thickly surrounded the balcony of the first tier along its entire length. The light aroma that reached the stalls left no doubt that roses are not a miracle of florist art. How many flowers did it take to make this – don’t forget to ask.

Kekhman took the novel of the same name by Dumas the Son as the literary basis for his production. The plot about the fate of a Parisian courtesan, largely based on autobiographical facts, was a great success among the writer’s contemporaries: just four years after the release of the novel, Giuseppe Verdi wrote the opera La Traviata, which to this day every self-respecting musical theater considers it an honor to have in repertoire. It also exists in Mikhailovsky – Gaudasinsky’s 1995 production. But Vladimir Kekhman wrote his own version of “Lady of the Camellias”: he changed the plot, the nature of the relationships of some of the characters, while maintaining their names (Margarita, Armand and Georges Duval, Baron Dufol), as well as the outline of the story. There is no trace of any consumptive courtesan, no trace of vice and its enjoyment in aristocratic salons. Everything is clean, airy, balletic. The action from Paris in the mid-19th century was transferred to St. Petersburg at the beginning of the 20th century, and specifically to Rossi Street, where a little girl, crouching in a modest curtsy, hands a letter to a gray-haired, respectable-looking gentleman.

And this same girl is already in a ballet skirt at the barre. In one scene she will live through three ages – a gifted little girl, a teenager who already skillfully bends and stretches her leg, and finally, a fully prepared ballerina who has recognized her first success. Growing up and learning takes place against the backdrop of several transparent curtains that act as a screen. On one, to the divine music of Verdi, ancient black and white photographs of young pupils of Agrippina Vaganova float, on the other – three or four graces in ballet exercises, right there – the streets of old Petersburg with Petersburgers of different classes, a tram, a horse with a cab… In a word, the Northern capital is before milestone year 1917. Historical video content (Vladimir Dulenko), both in content and technical execution, is subtly permeated with nostalgia.

Like, in fact, the whole story of the Russian ballerina Margarita: who survived emigration, the loss of her profession, and success. And love, as an opportunity to forget about losses and the inability to live without ballet art. Moreover, director Kekhman only indicates some of these stages – the silent movement of people with suitcases, like shadows, somewhere in the background, but he brings the essence of the actress’s life – ballet – to the forefront on the stage and shows it in large detail on the air screens.

Actually, the scene in the Parisian salon of the gray-haired gentleman, Baron Dufol, begins with the ballet, who practically does not leave the stage for two acts and is either a silent observer of what is happening, or his actions are driven by the old/new plot. The wonderful Sergei Leiferkus performs the role of the baron, and for the famous singer this is, in fact, a return to the Mikhailovsky stage, where he once began. His beautiful baritone and acting are certainly the highlight of the production. After the first show, backstage, Vladimir Kekhman thanked Sergei Petrovich for believing the aspiring director and following him.

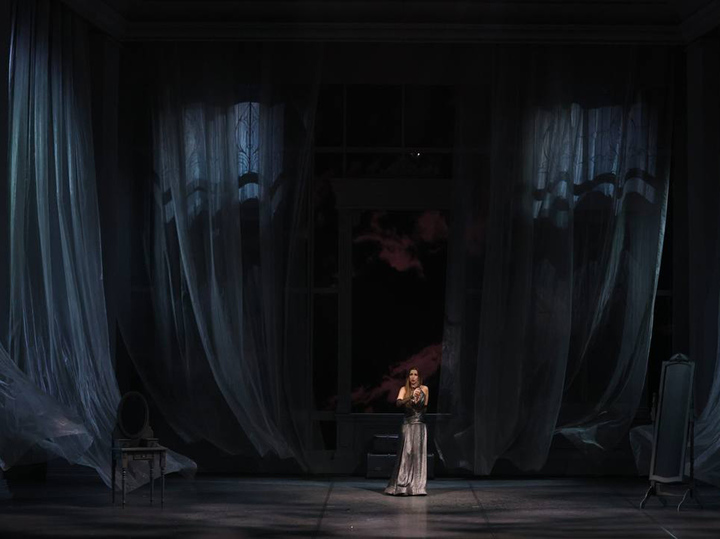

But let’s get back to the performance. It has a downright airy character, thanks in part to the scenography by Vyacheslav Okunev, who turned the Mikhailovsky stage into a light pavilion with high windows and flying transparent silk curtains. Where color and light – from light gray to heavenly in many shades – add purity and sensuality to the story of the Russian ballerina.

Yes, Kekhman, as a director, opens the opera with a ballet key and does it so persistently that the question arises: is this opera betrothed to ballet, or ballet to opera? Who would doubt that spectacular ballet divertissements, numbers to Verdi’s music (elegant choreography by Alexander Omar) performed by Mikhailovsky’s soloists and a guest star (every time they promise a new one) will decorate any opera performance. But in “Lady of the Camellias” the significant emphasis on ballet art in the opera is not just an element of decoration. For Vladimir Kekhman, who in his artistic strategy relies more on ballet, the artists’ injuries, operations with unpredictable consequences, not to mention the transience of the professional life of ballet dancers, became a reason for speaking out and a meaning for the sake of which it was worth starting with the production and entering into the slippery directorial path. It’s no secret that neophytes, as they say, with an open eye, often make unexpected moves and are intuitively able to create something interesting – the presence of talent is a guarantee of this. And Kekhman is a daring and talented person.

Together with the musical director of the production and conductor Alexander Solovyov, they very boldly created a musical edition of Verdi’s masterpiece. Thus, Margarita’s famous aria E strano is divided into two parts: the slow one sounds in the first act, and the fast one – Sempre libera – in the finale of the performance. In the second act, Armand’s aria and recitative conversations were removed (although I have seen this in other productions of La Traviata). But the rarely heard stretta No, non udrai rimproveri was left. Moreover, music by Tchaikovsky, Saint-Saëns, and, in the finale, Sibelius was added. Thus, in the second act, Baron Dufol turns the attention of his guests on stage and the audience in the hall to the left box, from where comes a violin solo (Olga Voronova), accompanying Irina Kosheleva, or in another composition, Priska Zeisel in the Russian dance from Swan Lake (choreography Kasyan Goleizovsky). She will be replaced by the invited prima from the Mariinsky Theater Ekaterina Kondaurova – she is incomparable in the image of the Swan in the choreography of Mikhail Fokin. The orchestra conducted by Alexander Solovyov sounded bright and emotional.

It must be said that the ballet frame for Verdi’s opera turned out to be like home, but… insidious for opera artists, especially for the performers of the role of Margarita: in different casts there are three of them – Alexandra Sennikova, Margarita Shapovalova and Daria Shuvalova. On the one hand, the public expects vocal prowess from the artists – and here, despite their youth, expectations were not disappointed. On the other hand, in order to be convincing in opera in the image of a ballet star, you need to match both external data and skill – here convention as a technique does not work. Therefore, before the premiere, the performers had to work at the barre with experienced teachers, and so far it can be stated that Alexandra Sennikova turned out to be the most flexible and convincing of all here. We can also congratulate Yegor Martynenko on his debut, who performed the part of Arman, for whom it was not easy to compete with the experienced and wonderful tenor Sergei Kuzmin, who sang on the first day. On equal terms were Alexander Shakhov and Semyon Antakov in the role of Georges, whom the directors for some reason did not age, and he was outwardly not inferior in age to his son. And, of course, bravo to the Mikhailovsky choir!

The final part is designed in a cinematic style: when the baron shoots Armand, who insulted Margarita, the scene freezes in a freeze frame. And then, to the alarming “Sad Waltz” by Sibelius, a figurine of a ballerina, which has become a symbol of Russian ballet, will appear on a transparent curtain. Photo of Margarita as a collective image of the stars of Russian ballet against the backdrop of the hall of the Imperial Theaters – bowing, strewn with flowers and alone, leaving in a luxurious long dress with a train.

The action returns to the starting point of the first act – the girl, the baron, the letter, the contents of which are voiced for the first time by the recipient. A woman whose days are numbered asks the Baron to be the patron of her gifted girl and explain to her that theater and ballet art are life – and only for their sake is it worth living. The performance ends with the aria “Sempre libera”. What Margarita chooses – here the directors leave the right of choice regarding the fate of the artist in exile to the viewer.

By the way, there were at least 10 thousand roses in the garland, and decorating the hall this way is a tradition at the Mikhailovsky Theater, but only for the premiere and only of Italian opera. This time the premiere coincided with the director’s birthday.

[ad_2]

Source link