The funeral of Silver Age poet Andrei Bely in the USSR was valued at 150 rubles

[ad_1]

An exhibition dedicated to the 90th anniversary of the day when the life of the “old regime” poet was cut short in Stalin’s Moscow was opened in Andrei Bely’s memorial apartment on Arbat. Three times called, by the way, in the newspapers a genius, and not a standard-bearer of empty and unprincipled poetry, alien to Soviet power, a singer of bourgeois decadence, or anything else.

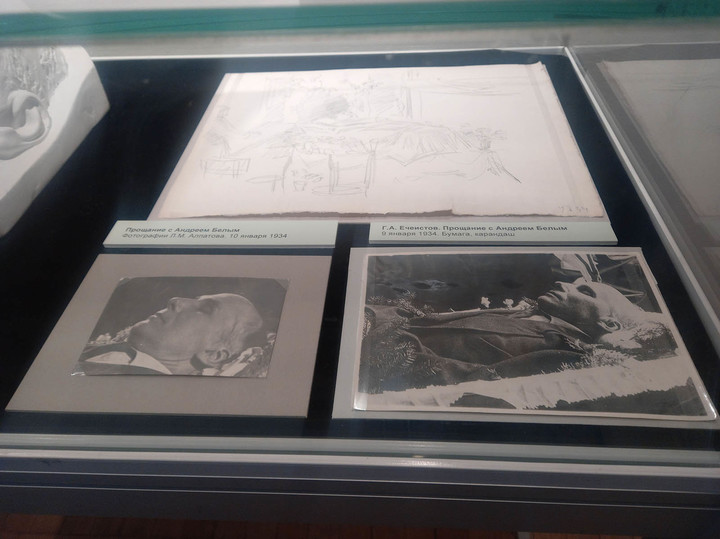

The organizers of the project “I’m so close to you…” deliberately selected from the funds objects and artifacts that literally reek of death. However, Bely was never afraid of it and was not afraid to pronounce it poetically. In 1908, in the poem “Death” of the same name, he wrote: “You are, you are young, you are young,/You are a husband… You are no longer there:/You were: and sank into the cold,/Into the silent abyss of years.” . He had to sink into this frightening abyss after a quarter of a century.

The semantic center of the exhibition is the death mask of Andrei Bely, although it is a copy of the original made by S.D. Merkulov in January 1934. But the originals are numerous drawings and pencil sketches from the mask and from the farewell and funeral itself by the artists Meer Axelrod, Georgy Echeistov and others. Thanks to them and photographs of individual authors and the “city committee of writers”, visitors see the poet in the coffin many times in detail. In some ways, the attention to his condition is even unnecessary; after all, Bely is not Lenin or another leader of the USSR.

But the detail did not interfere with another semantic layer – it remains to welcome the completeness of the obituaries presented here and abroad: in “L’Italia Letteraria”, “Literary Gazette”, “Izvestia”, “Evening Moscow” and “Literary Leningrad” (I immediately thought about “ MK”, but our newspaper was not published from 1931 to 1939). The clippings placed within not only document the era with 100% accuracy, but record the then style, state of the language and the accepted spelling of words.

We read: “The Organizing Committee of the Union of Soviet Writers (with capital letters!) announces with deep sorrow the death of Andrei Bely (the passport name and surname of the poet are given in brackets – Boris Nikolaevich Bugaev).” And further: “The civil memorial service will take place (there and then). Access to the body on January 9 from 4-10 pm. Also, the day of cremation will be announced (with an apostrophe, yes!) specially.”

“Andrei Bely might seem to belong to that intellectual stratum that is not on the path with the revolution,” but “now of the October Revolution … he defined his political views in detail, taking a place on our side of the barricades” – these are already quotes from the narrative part of the farewell article, signed by Boris Pilnyak, Boris Pasternak and Grigory Sannikov.

But let’s move on.

The illness, stay in the hospital and the tragic ending are also described in great detail – a recipe for injections from the First Moscow Clinical Hospital (dated December 30, 1933), an archival photograph of the buildings of the First Medical Institute, where Bely actually died, are presented. And also such tragic documents as a petition to the Writers’ Union to issue a bread card to the widow of Andrei Bely, Klavdia Nikolaevna Bugaeva. In 2024, when even the minimum wage can buy approximately 800 “social” loaves of bread (that is, about 400 kg), it is difficult to imagine what kind of value that decides who lives and who dies of hunger, like Marina Tsvetaeva, had this piece of paper.

And the most terrible artifact is a petition (again to the Organizing Committee of the joint venture) from a close friend of the poet Pyotr Zaitsev “with a request to pay for expenses incurred during the illness and funeral of Andrei Bely.” The right side of the paper is damaged and the numbers indicated are unreadable, so it is difficult to understand how much was given to the mortuary employees, the hearse attendants, the gravedigger (name illegible) for the mound, as well as the December “bill” for taxi rides to the doctors.

But the result in words “only one hundred and fifty-five rubles” can be guessed without discrepancies. Let me remind you that, according to the testimony of the French prose writer Andre Gide, in 1934 the average salary of a worker in the USSR was 180 rubles – and this was a humiliatingly small “pay”. But even less “labor” and “people’s” rubles were spent (specifically Zaitsev, and not all) on his final farewell to the classic of Russian poetry.

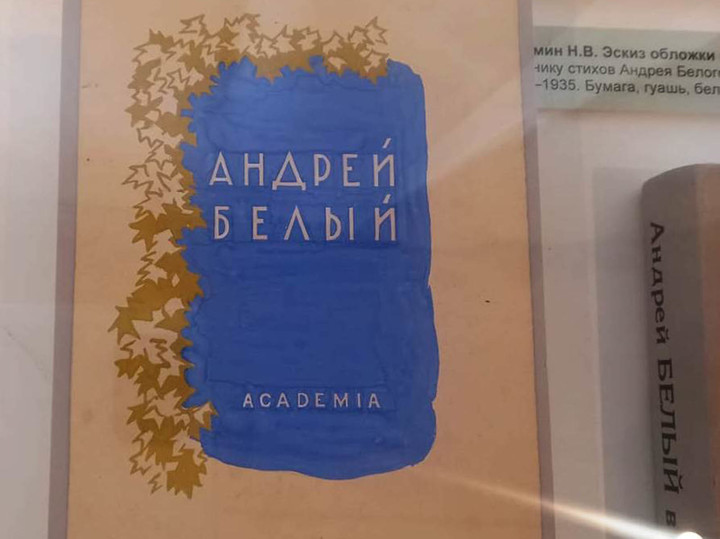

Acquaintance with this reality gives such a feeling of decay that the decadents and their followers would envy. The greatness of the legacy left by Bely, the things that belonged to him, carefully preserved by museum workers, recede before the stinginess of the world. Yes, I understand that he held in his hands this cigarette case, this cigarette holder, these tiny pencils, the size of a child’s finger, and created his great works with this particular pen, that the sketches of covers for his lifetime and posthumous books are unique, that the autograph of Mandelstam’s poetic dedication to Bely is not has prices. But everything is overshadowed by a loaf of black bread and other more “delicious” goods that the literary officials of Stalin’s time distributed among their own, protecting the world of rations from “alien elements.”

[ad_2]

Source link