Predictor of magnetic storms – Newspaper Kommersant No. 27 (7472) of 02/14/2023

[ad_1]

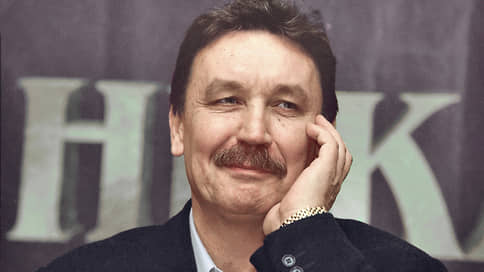

Vadim Abdrashitov, a film director who gave the most accurate diagnosis of the social diseases of the era of the late USSR and the first post-perestroika decade, has passed away. He was 78 years old.

Even at VGIK, he was already considered a rising directorial star with an impeccable Soviet biography. Father is a military man, mother is a chemical engineer. Impressed by Gagarin’s flight, he left Kazakhstan to study physics in order to study space. Driving through Moscow in the evening, I got to the shooting of “Nine Days of One Year” by Mikhail Romm – the spiritual father of many of the sixties. And when Vadim was already studying in his workshop at VGIK, having retrained from physicists to lyricists, Romm blessed his student and was even going to include his course documentary short film Reporting from the Asphalt in his montage epic film Still I Believe. And Abdrashitov’s diploma film “Stop Potapov!” (according to the feuilleton by Grigory Gorin, 1974) became a synopsis for the future disclosure of the phenomenon of Soviet conformism – even before the “Autumn Marathon” and “Flights in a dream and in reality.” Abdrashitov’s cinematography is also devoted to this theme, in its special turn.

A former engineer who rose to the rank of shop manager, Abdrashitov knew the ugly prose of life. But behind the mask of a social realist and truth-seeker was an artist with a much more subtle and complex structure.

His feature debut The Word for Defense (1976), as well as the follow-ups The Turn (1978), Fox Hunt (1980), The Train Stopped (1982), all based on scripts by Alexander Mindadze, confirmed the reputation and the class of the director, his unmistakable flair. These disturbing, far from complacency films were close parallel to the emerging Polish “cinema of moral anxiety”. They talked about the stuffy social climate, about how global goals disappear, blur and a person goes into private life, into the local world, but even there he feels out of tune with himself, his fate and his conscience. In the literature, this situation was thoroughly investigated by Trifonov, Abdrashitov gave her a screen life.

These films were so ingeniously constructed that they quite successfully (at least until Parade of the Planets, 1984) broke through ideological barriers. And although “Fox Hunting” was cut with censorship scissors, however, against the backdrop of many catastrophes that befell the sixties, the seventies Abdrashitov and Mindadze maintained an amazingly clear working rhythm: every two years, no matter what happened around, their new joint film appeared. This is, first of all, a movie of moral disputes, human, and hence acting duets. The cinema is predominantly and fundamentally masculine in terms of intonation and personnel. True, in the “Word for Protection” there are two actresses at the forefront – Marina Neyolova and Galina Yatskina. The first plays the defendant, the second – the judge, the first personifies the vital passion that led to the crime (she tried to gas herself and her unfaithful lover), the second – a boring life according to the rules of the metropolitan establishment (not only legal ones). But after the “Turn”, where Irina Kupchenko played an important role, women faded into the background in Abdrashitov’s cinema.

In Fox Hunt, Abdrashitov confronts the almost impeccable proletarian Belov (the amazingly authentic young Vladimir Gostyukhin) with the teenager Belikov (Igor Nefedov), who, together with his sidekick, attacked him in the park, took the blame (although he was less to blame) and one thundered to the colony. Belov goes to him with a vague inner goal to restore justice and, as a result, destroys his well-established life. Both heroes, for all their dissimilarity, are victims of a system of fetishes and fictions: hence the similarity of their surnames, for the same reason they are implicitly attracted to each other.

The film “The Train Stopped” is the pinnacle of Abdrashitov’s pre-perestroika period. His directorial style becomes all the more obvious classical mastery, the more Soviet the realities of a provincial town look, where a platform rolled away from the station and crashed into a passenger train, killing the driver. A visiting meticulous investigator (Oleg Borisov) finds out the circumstances of the accident – and runs into an ideologically biased journalist (Anatoly Solonitsyn). A typical Abdrashitov-Mindadze counterduet emerges – a confrontation between two men on an emotional, intellectual and social level. As a result of their debate, it becomes clear that everyone is to blame – from the track worker to the dead driver, to the management of the depot and the city, who want to replace the truth with a myth – the “feat of the driver” who saved the passengers at the cost of life. The theory of exploits in peacetime as a means of camouflaging bungling and collective irresponsibility could be considered a Soviet phenomenon if it had not successfully survived perestroika and did not fit into the new Russian realities. That’s why Abdrashitov’s best film lives on.

Abdrashitov always had a penchant for the grotesque, but it openly came out in the Parade of the Planets. And the “creeping realism” of the director’s early works is an illusion.

Behind scrupulous everyday life they always feel a chill of transcendence, behind social routine – explosive instincts, behind the roles established by society – deep human essences that are by no means in statutory relations with each other.

“Plumbum” (1986), “Servant” (1988), “Armavir” (1991) are the next stages of the director’s path. Their charming eclecticism betrays a conscientious effort to keep pace with artistic progress, with the winds of postmodernism. In “Plumbum” – a film about the modern Pavlik Morozov, who took on the role of a “nurse”, a fighter against offenders – they found an echo with the grotesques “Oh, lucky!” Lindsay Anderson and Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange. But even here in Abdrashitov’s spectacular symbols and hyperbole, our sinful reality emerges.

In “Armavir” the director moves towards a global metaphor, which was easily deciphered in the light of the death of “Admiral Nakhimov” – this Soviet “Titanic” – and the collapse of the USSR that soon followed.

In 1994, “A Play for a Passenger” appeared – also a metaphor, but local, closed in the space of the train. Again, two heroes are tightly connected by a thread of fate – the Passenger (Igor Livanov), a once intelligent swindler, now a criminalized businessman, and the Conductor (Sergey Makovetsky) – in the past the same judge who broke his life: broken kidneys, a destroyed family, a dead child. In the finale, we, together with the Conductor, see his double in the window of a passing train – and we understand that it is impossible to settle accounts with the past: a whole army of unified servicemen stands guard over him, and no one is responsible for anything. So, again with a metaphor associated with the train, Abdrashitov completes his analysis of the perestroika campaign. Everything has turned upside down in the country, but there has been no real change of roles: the soulless nomenklatura Conductors are still leading a train with disenfranchised Passengers to nowhere.

Another metaphor is offered by Abdrashitov and Mindadze in the film Dancer’s Time (1998). This is a movie about the unsteady peace that came after another of the Caucasian wars. The unwitting hero of our time is a dancer from the Cossack ensemble: he embodies the false and selfish essence of modern “hybrid wars”. “Magnetic Storms” (2002) is the last joint film of Vadim Abdrashitov and Alexander Mindadze. And the last film of Abdrashitov. It starts with a fight: wall to wall, two crowds of men advancing on each other. No words, no music, just the noise of disorderly fuss. Bodies with tensed muscles converge and diverge, torture and beat each other “on the bowler hat”, chained to the machine vise without any meaning or purpose. And just as the figures of unfortunate fighters, the “fierce friends” are caricatured and absurd – the masters of life, directing this animal nonsense, this is the Brownian movement of the crowd. For twenty years now, this ominous prediction has sounded from the lips of Abdrashitov. And the further, the more obvious that it comes true.

[ad_2]

Source link