how “Moscow – Cassiopeia” and “Through Thorns to the Stars” were made

[ad_1]

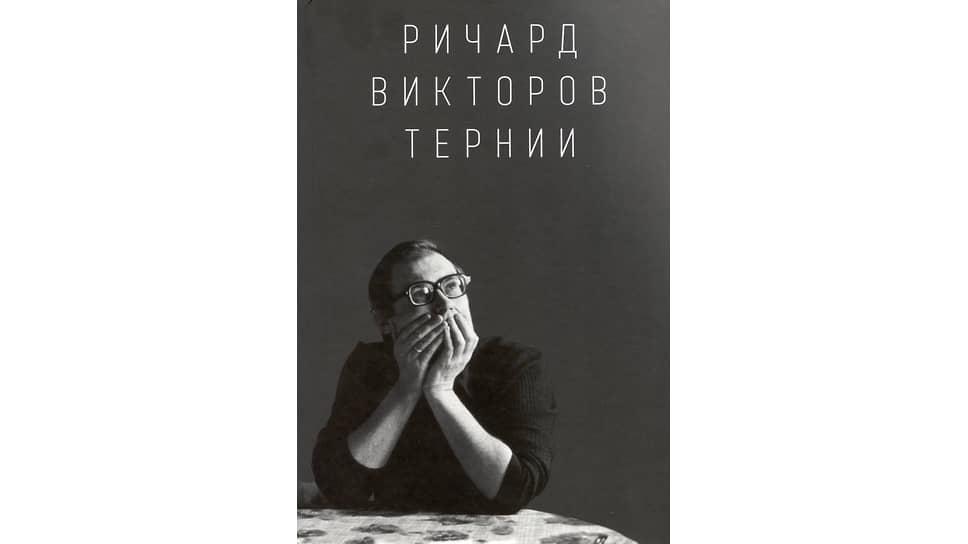

The publishing house “Zebra E” published the book “Richard Viktorov. Thorns” is a monumental volume that has been in preparation for several decades, dedicated to the author of “Moscow – Cassiopeia” and “Through Thorns to the Stars.” This book, collected by Viktorov’s widow and beloved actress Nadezhda Sementsova, as well as their children, includes fragments of diaries, work notes, letters, memories of colleagues and loved ones. It makes it a little clearer how this realistic director suddenly turned into a virtuoso master of fantasy, who, like no one else in Soviet cinema, knew how to combine fun with high pathos.

Since the 1950s, space has become one of the main sources of inspiration for Soviet culture. The point is not only that the space program was the most visible and spectacular success of the USSR, but also in the special load of the space myth. Space was the promise of the future, and therefore in culture it served as a kind of substitute, a metonymy for the unimaginable communism. Despite all this, successful works of Soviet space science fiction can be listed on one hand: “Planet of Storms” by Pavel Kulushantsev (1962), “The Mysterious Wall” by Irina Povolotskaya (1967), “Solaris” (1972) and “Stalker” (1979) by Andrei Tarkovsky , “Hotel “At the Dead Climber”” by Grigory Kromanov (1979), “Kin-dza-dza!” Georgy Danelia (1986), as well as three paintings by Richard Viktorov – “Moscow – Cassiopeia” (1973), its continuation “Youths in the Universe” (1974) and “Through Thorns to the Stars” (1980). For most directors who tried their hand at science fiction, it was a genre experiment. For Viktorov it became a matter of life.

When Viktorov took on “Moscow – Cassiopeia”, he was already an established director, the author of six films: the socialist realist idyll about lumberjacks “On My Green Land” (1958), the detective story “A Sharp Turn Ahead” (1960), the military trench film “The Third rockets” (1963), teenage dramas “Beloved” (1965), “Coming of Age” (1968) and “Cross the Threshold” (1970). He had his own developed style – lyrical realism with a slightly moralistic tinge. The transition from him to interplanetary flights and insidious robots looks strange. What seems even more unusual is that after all these quite worthy, but not at all outstanding films, Viktorov suddenly shoots real masterpieces.

Photo: Zebra-E

Viktorov took up science fiction almost by accident: he accidentally came across the script for “Cassiopeia” by Avenir Zak and Isai Kuznetsov (masters of the teenage genre who wrote, for example, “Property of the Republic” by Vladimir Bychkov (1971)). By the time Zak and Kuznetsov are writing their story about the rescue of a distant planet by Soviet schoolchildren, dreams of contacts between the inhabitants of the Earth and other worlds, so beloved by the authors of the Thaw, were living out their last days. In the same 1972, when “Cassiopeia” was filmed, the Strugatsky brothers, the main singers of contact in Soviet literature, were just writing “Roadside Picnic,” in which the meetings of humanity and space civilization turn out not even as a disaster, but simply as a gloomy misunderstanding. Simultaneously with the first part of Viktorov’s dilogy, perhaps the last Soviet film was released, seriously telling about the meeting of earthlings and carriers of alien intelligence – “The Silence of Doctor Ivens” by Budimir Metalnikov (in Tarkovsky, Kromanov, Danelia, it is still obvious that we are talking about earthly affairs, and space is a pure metaphor). The idea of Metalnikov’s painting: nothing will come of this meeting, earthlings are not ready for the gifts of space, they are corrupted by violence, it is better to stay away from each other. The film took place somewhere in the West, but this generalization easily extended to all of humanity, including the USSR.

Why is Viktorov taking on this rapidly becoming obsolete topic? It seems that he was not too interested in the secrets of the universe, the conquest of outer space and the meeting of man with representatives of other worlds. He was interested in another thing – the future. Judging by all his early films, memories of him and the director’s own texts, Viktorov perceived cinema as a pedagogical tool, a means of education, reminders of ideals, lofty goals and the dangers that lie in wait on the way to them. Pathos was his element, but he truly revealed himself as a director precisely when the pathos of concern for the future began to gradually die, disappear from Soviet art, giving way to irony and melancholy; they stopped believing in the future. Viktorov’s films act so charmingly strange precisely against the backdrop of this disappointment. Speaking about the future, he is actually trying to delay, to rewind time a little.

If the distant future in the system of Soviet culture was represented by a cosmic myth, then the near future was embodied by children – those who will live in a better world that is being built now, those who are responsible for it. The idea of Zach, Kuznetsov and Viktorov was to combine these two images and send children into space. In the plot of the film, this enterprise has a scientific motivation: earthlings want to respond to a distress signal coming from a planet in the constellation Cassiopeia, but flying there takes decades, adult cosmonauts simply won’t make it, and children will arrive in the prime of life. The heroes, however, miraculously overcome the barrier of the speed of light and in the second part of the dilogy, “Youths in the Universe,” they find themselves on the planet Varian at the age of thirteen or fourteen.

Variana is a techno-utopia that turned into a dystopia: its inhabitants created robots that perform all tasks, including controlling other robots, but, having gained consciousness, the machines decided to get rid of their masters and restore perfect order. They did not kill them, but made them absolutely happy, blocked desires, cravings for something new, and thus doomed them to extinction. Children, just discovering the world of great feelings and actions, are ideal for resisting such a violent craving for happiness, only they are capable of starting a revolution and overthrowing the power of robots. The worldview at work here comes from the Thaw: progress is good, but it is nothing without daring, impulse, that is, without communist subjectivity, which makes the inhabitants of the present involved in the future.

This worldview also determines the aesthetics of Viktorov’s fiction. Both the duology about Cassiopeia and the developing motifs “Through Thorns to the Stars” are filmed in a unique fresco style: the characters freeze in heroic poses, look into the camera, uttering loud phrases; the frame often almost resembles an icon. This style arose from the cinematography’s adaptation of the “severe style” techniques of Thaw painting. This is how historical-revolutionary dramas of the 1960s were filmed: “Optimistic Tragedy” by Samson Samsonov (1963), “First Russians” by Alexander Ivanov and Evgeny Shiffers (1967), “Commissars” by Nikolai Mashchenko (1969). In the 1970s, both this aesthetics and the ideology behind it already looked obsolete. But, as often happens, what dies in adult art can exist quite organically in children’s and teenage art. Space films for young people turned out to be an opportunity for Viktorov to revive his dear Thaw sensibility.

This revival had its price. Viktorov understood: in order to revive the art of high pathos in an era when pathos is no longer believed, irony must be instilled in it. That’s why there are so many eccentricities in his films: ridiculous clothes and gaits of robots, phrases like “we are defective, we are your friends,” an alien scientist in the guise of a grumpy octopus and the ominous dwarf Turanchox in “Thorns.” The sublime works only in conjunction with the ridiculous; You can tell the highest truth about a person only by speaking not entirely seriously.

Viktorov’s last completed film, “Through Thorns to the Stars,” written by him in collaboration with Kir Bulychev, is his best, wittiest, but also most desperate film. This is a laboratory experiment in the production of high pathos. The android girl Niya, literally created in a test tube, becomes the perfect hero, the savior of the planet from environmental disaster and merciless capitalism. “Through Thorns to the Stars” is an absolutely toy film and at the same time extremely sublime. This is something like a fantastic mystery, a picture of a revolutionary feat, but told not even as a metaphor, but as a fairy tale with evil gnomes and talking animals. In 1980, in an era of deep stagnation, it is no longer possible to imagine a person capable of such a feat – even a person of the future, even a child. Only a beautiful alien homunculus. It is here—in the demand for an ideal and the ability to play it out only in an almost parodic form—that the hidden drama of Viktorov’s cinema is found.

Subscribe to Weekend channel in Telegram

[ad_2]

Source link