At the exhibition about Kashtanka, the house of trainer Georges was glued together and an ancient lantern was “frozen”

[ad_1]

A doll’s house according to Chekhov

The State Literature Museum ends the calendar year with an exhibition about Kashtanka, without which it is difficult to imagine Russian literature for children and Russian theater. 2023 is, first of all, the year of the 125th anniversary of the Moscow Art Theater. Chekhov, so any project automatically rhymes with this “Chekhov anniversary”. But GMIRLY has his own starting point: 135 years ago, in a house on Sadovo-Kudrinskaya, Anton Pavlovich wrote an immortal story. The MK correspondent went to the old mansion, where one of the main Chekhov museums has been operating since 1954, on a day when the same fluffy snow fell on Moscow as fell on the back of a frozen lonely dog.

When you go to a literary exhibition, the first thing you do is assess what age audience it might be of interest to, other than the adult conscious connoisseur. Recently, in the House of I.S. Ostroukhov in Trubniki, two halls were filled with exhibits telling about the life and literary heritage of Viktor Dragunsky, with an emphasis on children’s books, school subjects and toys of the USSR of the mid-20th century. That is, if you go there with a child 4–7 years old, a preschooler or a first-grader, he, if he has innate curiosity, will be delighted. The project “Kashtanka: the story of a young red dog” is addressed primarily to that age whose owner most often cannot read himself, loves color pictures and shouts in admiration: “Mom, look, a dog” when he meets a four-legged pet on the street.

It is most convenient to look at the two “doll houses” presented there – the house of the carpenter Luka Aleksandrovich and the mansion of the circus performer Georges – if the height of the viewer is no more than a meter. Everyone else will have to bend over.

But the detailing there is Swiftian – a room measuring 25 by 25 centimeters fits a machine tool, wooden blanks, a tiny plane, a saw, a hacksaw and a kerosene lamp, and the whole room is densely strewn with shavings (a little out of scale, but the atmosphere of the workplace is conveyed perfectly).

And in the trainer’s front room, a carpet, rich furniture, a portrait on the wall, a chest of drawers and a table lined with china the size of a little fingernail await us. And in the room where the “mysterious stranger” Georges trained the cat Fyodor Timofeevich, the goose Ivan Ivanovich and the pig Khavronya Ivanovna, they recreated the “letter P” with a crossbar on which a bell and a pistol hung, where “ropes stretched from the tongue of the bell and from the trigger of the pistol” – so that the smart goose gives a signal about a fire and fires a shot.

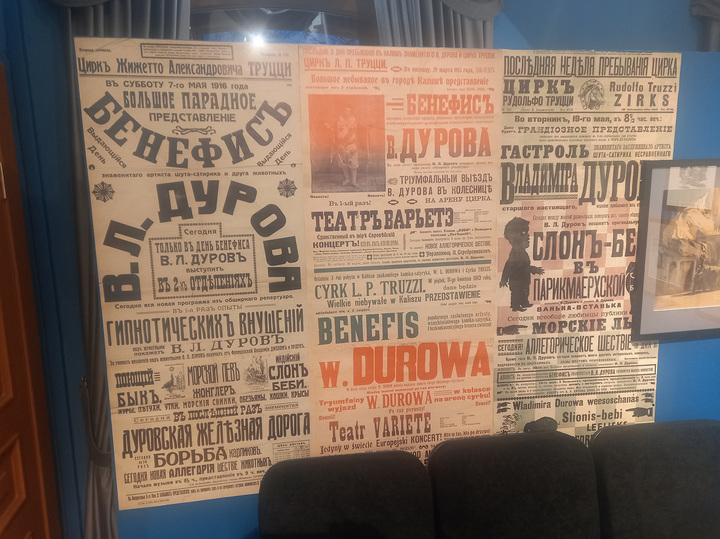

In general, such exhibitions are not supposed to be visited separately – they seem to serve as a “bonus” to the main exhibition, so “Kashtanka…” cannot boast of its scope. But something extremely curious is that it has a winter lantern on it – so realistic that you want to try to touch the metal with your tongue “in the cold.” Plus about three dozen illustrations by artists Dmitry Kardovsky, Vasily Ponomarev, Sergei Alimov and Anatoly Itkin, a 1926 film poster, the writer’s autographs, including a dedicatory inscription on the lifetime edition of “Kashtanka”, copies of letters. And in significant quantities – circus posters from the beginning of the last century, both associated and not associated with the name of Vladimir Leonidovich Durov, the great trainer who, according to one version, served as the prototype of Chekhov’s Georges.

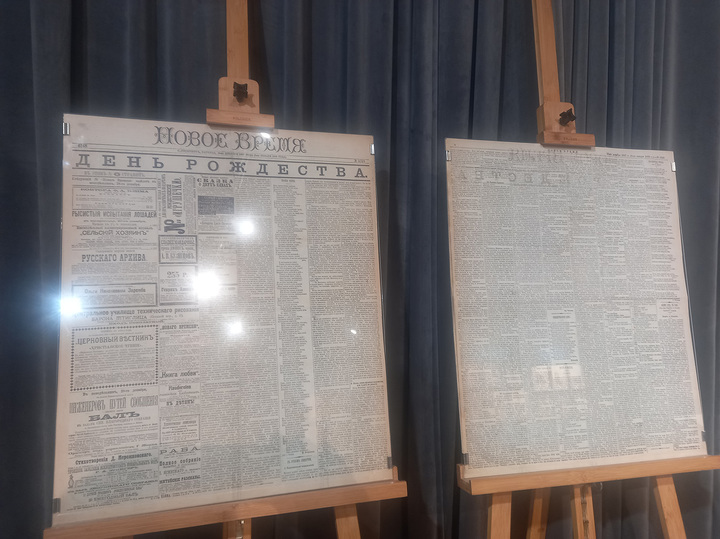

But exhibit number one is the newspaper “New Time” for December 25, 1887. When publishing a modern newspaper (such as MK), it is difficult to imagine that our predecessors of the 19th century devoted half of the front page to a literary work. But here is the proof – a few broadcast advertisements, poetry, and then neat letter columns and the heading: “In a learned society” (in the old spelling, of course). At the end there is a modest signature: “An. Chekhov.”

[ad_2]

Source link