Alexey Fedorchenko made a film about the Caucasus, which began with the love of a Chechen Chekist

[ad_1]

Two years ago, at the Message to Man festival, Alexei Fedorchenko told MK about his new idea, Big Ulli-Kale Snakes. Now the world premiere of the film took place in St. Petersburg, and its author is being asked where exactly he managed to find a treasure with pre-revolutionary films that can change the course of the history of world cinema.

After the premiere, Alexei Fedorchenko, who directed the films “Oatmeal”, “Heavenly Wives of the Meadow Mari”, “Angels of the Revolution”, “Anna’s War”, “The Last Dear Bulgaria”, is almost our only director who has mastered the genre of mockumentary (pseudo-documentary films), was awarded award for outstanding artistic achievement. In 2005, at the Venice Film Festival, he was awarded the prize for best documentary for the feature film First on the Moon about the Russians who landed on the moon under Stalin. If the professionals are already seduced, then what can we say about ordinary viewers.

Once, at the Message to Man, Alexei presented the non-fiction Wind Shuvgei, which tells about the development of Siberia in the 1960s by the Bulgarians, who sang Kalinka, cooked lecho, and then they seemed to be blown away by the wind. This time they showed not only “Big snakes of Ulli-Kale”, but also the documentary “Coin of the country of Malawi” about the Shukshin holiday in Strostki and the African state, where coins with the image of Vasily Makarovich are minted. Someone does not believe in anything, even the existence of the country of Malawi. Some take the most incredible things at face value. Fedorchenko worked on the film about Shukshin for 3 years, and 8 years have passed since the idea arose.

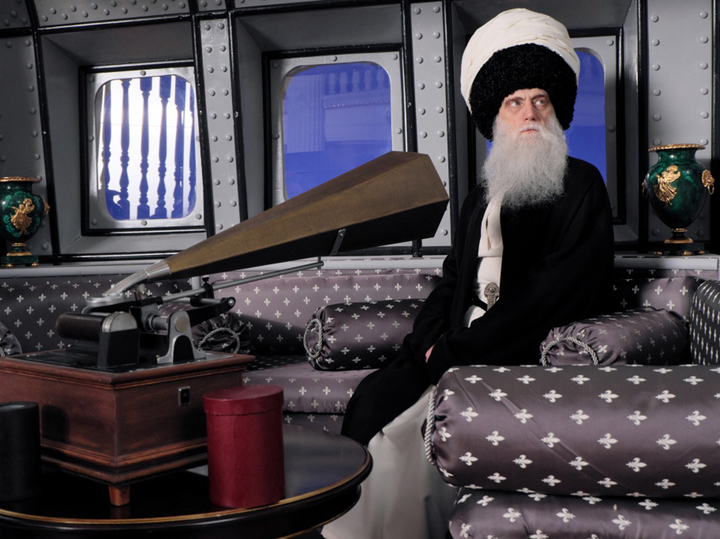

In the title role, although we are talking about documentary films, he himself shoots on the phone, talks with Shukshin’s fellow countrymen. Fedorchenko will continue his acting experience in The Great Serpents of Ulli-Kale, where we are already talking about how relations between the Caucasus and Russia developed at the beginning of the 19th century and up to the beginning of the 20th century. Among the actors are Pushkin, Lermontov, Leo Tolstoy, Gogol, Alexander Dumas, Vakhtangov, Sufi sheikhs, Shamil. Aleksey Uchitel, presenting the award to Aleksey, said that his film could be included in the feature, documentary, animation and experimental programs.

“From one old book, I learned a story about a Chechen Chekist who terrorized, killed, burned, poisoned people in the 1920s,” says Alexei Fedorchenko. He saw the girl and decided that she should become his wife. He went to fight with the Basmachi, punishing him so that no one would touch his chosen one. The elders decided why on earth someone from Grozny would point out to them when there were enough of their good guys. A young handsome guy kidnapped a girl, took her to the mountains. And when the Chekist returned, he caught a couple and sent them to prison. The elders warned: there will be a riot, people will come out with weapons. I suggested that my co-author Lida Kanasheva write a western. I thought that if our heroes got married somewhere in 1920, then they probably lived for another 40-50 years. I found an unusual golden grave, to which people from all over Chechnya and Dagestan go to worship. It turned out that our heroine was the daughter of a Sufi sheikh revered in Chechnya. We began to study how Sufism appeared there, how the Caucasian war began, who Shamil was. We relied on different sources, on the works of Caucasian philosophers, records of Shamil’s conversations, reached Chechen paganism, until 1913, when the story of the Chekist with the girl began. Episodes that seem fabulous, such as Pushkin’s, are in fact documentaries based on a quote from Tolstoy. There is not a single false story in our film. It’s just that the truth is so amazing that it looks like a fairy tale.”

“Big Serpents of Ulli-Kale” was filmed in Chechnya, Adygea, Ingushetia, North Ossetia, mountain villages and the Karmadon Gorge, where the crew of Sergei Bodrov died, the city of the dead, which makes a strong impression on the screen and in reality. The film begins with a film crew led by Fedorchenko extracting from the ground boxes with half-decayed pre-revolutionary films made by nine directors. Aleksey Taldykin buried the negatives, fearing their destruction by representatives of the Soviet authorities. This man himself is not a phantom, but a real merchant, a pioneer of filmmaking. In 1913, in his film studio with Drankov, the film “The Conquest of the Caucasus” was created, which was later shown to the royal people in Livadia. If those films had appeared earlier, the history of world cinema could have taken a different path, and Joel Chapron, a delegate of the Cannes Film Festival, authoritatively confirms this in the frame. And Fedorchenko himself appears on television, talking about priceless finds. After the premiere, viewers are interested in exactly where the treasure was dug up. As the hero of another film, Fedorchenko, says, if it was filmed, then it was.

Theater director Nikolai Kolyada appears as a prominent Gogol scholar. There is some wild story on the screen about Gogol’s hat, which has become a landmark of Kaluga, and a newborn in the Caucasus is given the strange name Kaluga. Tolstoy bails out the young Lezgin, and when the writer is dying, his inconsolable wife is told: “He was going to the Caucasus, Sofya Andreevna.” Wherever you stick, everywhere is the Caucasus. All roads lead to this. An episode with the participation of Georgy Iobadze, who was recently almost torn apart for the role of the young Stalin in the performance of the Moscow Art Theater named after M.I. Gorky “The Wonderful Georgian” with the participation of Olga Buzova. With Fedorchenko, he famously fit into the elements of the fantastic Caucasus and our ideas about it.

The film was originally shot in black and white, but the footage looked boring on screen, so they switched to color. Some of the frames were hand-colored, referring to the techniques of silent cinema, they were stylized as an old film. As Fedorchenko will say, color cinema of the beginning of the century turned out to be more truthful than black and white.

Newspaper headline:

Chechen Chekist never made it to the movies

[ad_2]

Source link