Entrance to the darkness – Weekend – Kommersant

[ad_1]

The porn industry of the film era in the cultural memory is colored in tones of nostalgia. The space of experiment and revolution, sentiment and otherness, idealism and freedom – this is how cinema often shows it. Even more loaded with these romantic meanings is the location of the cinema for adults – a bygone nature in which the very ontology of cinema crystallizes.

A movie theater on a movie screen is an oxymoron. Nevertheless, this image seems to be the ultimate expression of the essence of cinema, a media doomed to forever peer into its own reflection. So, in any case, thought the French theorists of the 70s, forever bygone era of revolutionary idealism – and the golden age of film porn.

What does the camera see, looking into the hall of the porn cinema? Collective agitation, like in Hertz Frank’s film “10 Minutes Older”, filmed in the hall of the puppet theater? Not at all: more often than not, she faces blank zombies, figures in a trance, staring catatonically out of the darkness. Exactly this frame opens one of the few existing feature films about the porn industry, shot by Bertrand Bonello’s “Pornograph” (2001): the audience, rarely seated in the hall of the Parisian “adult cinema”, is the least like living people. What they wandered into this room for, a film made by the protagonist, an aging master of the low genre, who retired from the profession in the mid-80s (the time of the video expansion), will not be shown to us. And why? As will become clear later, in the films of maestro Jacques Laurens (symptomatically played by Jean-Pierre Leo, himself a living symbol of cinema), the main thing was not what was shown, but what was hidden. And even more than that – in what is not an object of vision, but becomes a subject, looking back into the hall. An invisible something coming from the eyes of the actress – not passively perceiving, absorbing, but penetrating, like a laser beam. The same gaze, about which so many copies have been broken and which can pierce not only the figure on the screen, but also strike the heart. Of course, only on the big screen.

And the camera avoids this view as much as possible. The fear of the modern viewer before such a test – before destroying the safe distance between the chair and the screen – is directly articulated by Bonello: when the hero Leo suddenly receives an order to shoot a film and tries to work according to the rules of the old school, requiring the actress to look at the camera, to replace the body with her gaze, his quickly replaced by a rookie.

And now, turning away from the screen, we cast our passive gaze over the space of the cinema for adults: like any wrong side, it is dilapidated, sad, marked by traces of time and infected with disputes of nostalgia. The logic of the traditional film business does not imply a reverse flow of time. Re-releases and retrospectives in the era of film were localized in the oases of museums and cinematheques. And outside this boutique space, old cinema is the bearer of a kind of curse, just as old films are the abode of spirits; Is it possible to watch vintage porn like porn, knowing that all the people on the screen are already dead?

***

Viewers of this movie are at risk of acquiring ghostly status themselves. The hontological nature of the film, which Olivier Assayas constantly insists on in his work, and the strange sexual aura of decay form the perfect match. This is well illustrated in Cai Ming-liang’s Dragon’s Sanctuary (2003), where an old, demolished movie theater that plays 1950s wuxia movies serves as a cruising destination for Taipei’s gay underground. While on the screen the deep past wiggles with false mustaches, they rustle in the darkness of the spitting hall – like ghosts! – casual lovers, sex workers and their anonymous clients. It is possible that the cinema is basically invented precisely as a shadowy space of sex/sexuality, and not of culture. The movie date tradition, the cliché of touching hands in the dark, “kissing spots,” drive-ins (there’s a doubling going on: the movie theater meets the baby boomer generation’s main sexual gadget, the car). The main thing is that the screen should be dark enough. And what goes there is the third question.

***

From Taipei we are transported to Manila, already in a real cinema for adults – the main setting of “Serbis” (2008) by Brillante Mendoza. This is a paradoxical space in which the private becomes public and vice versa: a shabby building with rounded sunscreens is in fact a home for a large family of owners: they cook here under the stairs, dine in the foyer, have sex in the mechanic’s booth, in a giant empty hall — sad. But in the evening, a motley crowd quietly crawls into the hall – young and old, residents of the capital and visitors, gays, trans, female prostitutes. They stand along the walls, sit down to the audience and offer “service”. All of them bear a strange stamp of doom: this hall is also their last refuge, apparently doomed to an early disappearance along with film projection, hand-drawn posters of naked beauties and calligraphic graffiti on the walls. What is on the screen is no longer important: no one except the mechanic pays attention to the goat that accidentally jumped onto the stage in front of him. He turns on the light, and the cave of pleasure turns into a messy kitchen. Buttoning up their pants in a panic, turning away from each other, the visitors deanonymized by electricity flee from the hall. The same heavy awkwardness, but masked by the aforementioned ceremonial catatonia, reigns at the very first sessions of obscene cinema (porn and cinema are the same age), shown by Balabanov in “About Freaks and People.” Excess and transgression clearly require a separate space, they must be forced out of furnished rooms and offices, where there are neither books nor ficuses in tubs.

***

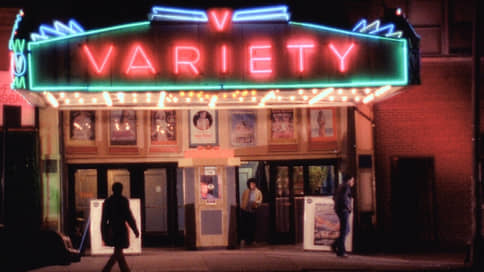

What can wait for someone else in this secret club for their own? Shock and transformation – most likely fatal. The evil magic of porn is present even in a place as shabby, devoid of charm and aura as a porn cinema in the dirty Times Square of the early 80s. In Bette Gordon’s Variety (1983, credited as half of New York’s punk scene, from Kathy Acker to Nan Goldin), the ironically named Variety, the namesake of the famous glossy magazine about the Hollywood movie business, simultaneously becomes the territory of seduction and obscene in its prosaic alienation of labor. The main character Christina, desperate to find a normal job, goes here to work as an usher and spends hours toiling from idleness in her closet. In order to somehow have fun, she begins to look into the hall and one day she meets a mysterious white gentleman in the lobby, his outfit standing out against the background of the usual crowd of visitors, colored men in jeans and sports jackets. Driven by a dangerous curiosity, she goes on a date with a stranger, then begins to follow him – and discovers his connection to the mafia. A suicidal attraction turns her into a real stalker – but the terrible mystical secret that Christina faces does not concern him, but herself. Plunging into the labyrinths of sex shops and Times Square peep shows, she discovers with amazement in magazines, on posters, on the screen of her own cinema … herself? We will never understand that this is a fantasy, a coincidence (double), but the surreal displacement is very symptomatic. The porn cinema becomes the entrance to the Looking Glass, from where there is no way back. The film ends with a shot of an empty, wet intersection where Christina and a mafia stranger were supposed to (should?) have a nightly date – an allusion either to noir, or to the finale of Antonioni’s Eclipse, another masterpiece dedicated to the tossings of the bourgeois soul and the doom of the search for love. and adventure.

This entourage – a dim lantern, a spot of light, a drizzle of rain – seems to be a metaphor for infinity, an extensive filmography of films that began or ended at the same crossroads. Whereas the cinema – any – is the other side of the same setting: this darkness surrounding the bright spot of the screen is a cemetery where all the films of the world are buried. The abyss literally appears at the end of “Serbis”: the film film starts to burn right in the middle of the dialogue scene of the characters, and the black crater slowly spreads over the entire screen.

Subscribe to Weekend channel in Telegram

[ad_2]

Source link