A ray of color in the dark realm – Weekend – Kommersant

[ad_1]

On September 18, the exhibition “Grigory Gidoni and his New Art of Light and Color” ends at the Na Shabolovka Gallery. Together with the exhibition, the history of a unique institution that arose on the basis of one of the regional exhibition halls of Moscow ends. This coincidence seems to be symbolic.

No, at the end of the exhibition about Grigory Gidoni, the exhibition space in one of the houses of the Khavsko-Shabolovsky housing estate will not close, it will continue to function as part of the Moscow Exhibition Halls association. But that gallery “On Shabolovka” will disappear, which since the mid-2010s began to turn into an ark for everything that was ousted from the great history of pre-war Soviet art – in marginalia and footnotes. The curator, Alexandra Selivanova, leaves the gallery, and she, like a real captain, is the last to leave the sinking ship – the team she assembled has already left. All-consuming bureaucratization, measuring efficiency in the number of tickets sold and school groups, tight control over the plans of exhibitions and events – in recent times, the liberal spirit has completely disappeared from the system of regional exhibition halls that appeared as a result of Kapkov’s reforms in the cultural sphere of Moscow. Last year, for example, two halls that had “their own identity” lost their bright leaders and were “reformatted”: the artist Andrei Bartenev had to leave the gallery “Here on Taganka”, which under his leadership turned into a vibrant center of youth street art culture, artist Aristarkh Chernyshev from the Electromuseum in Rostokino, which has become an experimental platform for new media, noticeable on an international scale (even the famous Austrian festival Ars Electronica collaborated with them). This year has brought new requirements – to make a dossier on artists and curators on the subject of trustworthiness. By and large, all the artists whose legacy the gallery “On Shabolovka” worked with were unreliable and somehow fell under the rink of Stalinist repressions: some – Grigory Gidoni, Alexei Gastev, Oberiuts – were shot or killed in prisons, others were struck out of the profession and from stories. Gallery “On Shabolovka”, in fact, dealt with white and blind spots in the history of the Soviet avant-garde of the 1920s and 1930s.

Alexandra Selivanova, an architectural historian, curator and museum educator, came to Shabolovka in 2014. Initially, it became the district library, which soon merged with the district exhibition hall to become a center for research and popularization of Soviet pre-war modernism, which fell out of the simple scheme of “avant-garde stopped on the run” versus “totalitarian art”. By that time, Selivanova already had a reputation as a curator who knew how to make large and spectacular exhibitions like Avant-Garde and Aviation at the Jewish Museum and Tolerance Center – it seemed that she would be cramped in the tiny Shabolov halls. She continued to work on large projects – for the Museum of Moscow or the Moscow Museum of Modern Art – as part of various curatorial teams: Moscow Thaw: 1953-1968, Fabrics of Moscow, Gorky Park: Factory of Happy People, VKHUTEMAS 100. School avant-garde”, “Electrification. 100th Anniversary of the GOELRO Plan” — all of these were key events in Moscow’s exhibition history in recent years. But for all their showiness — hundreds of items from the country’s main museums, avant-garde design, elements of theatricalization — each of these exhibitions was a research work that revealed forgotten names and little-studied aspects of the Soviet modernist project, and was accompanied by an extensive educational program.

The exhibitions “On Shabolovka”, made by Alexandra Selivanova herself, in curatorial alliances or by like-minded curators such as Nadezhda Plungyan, partly overlapped with these large projects, but with a much more modest size and budget, they were even more complex and sophisticated studies – with the involvement materials from private archives and collections. Moreover, the educational program – excursions, lectures, concerts, performances, classes in children’s studios – made these studies interesting not only for a narrow circle of specialists. A circle, meanwhile, has also developed – both humanities scholars and artists turning to the Soviet avant-garde (the gallery periodically arranged exhibitions of contemporary art or design). But more importantly, the gallery’s non-professional audience learned to appreciate and protect the constructivist monuments of Moscow, starting with the Shukhov Tower, which was planned to be moved from Shabolovka just in 2014. The first Shabolov exhibitions were devoted to avant-garde architecture – this perspective was suggested by the genius of the place itself: the gallery was located in the former public center of the Khavsko-Shabolovsky residential area, the only project implemented in Moscow by the rationalist architects of the ASNOVA brigade (in 2017, “On Shabolovka” showed an excellent exhibition about the rationalist ideologist Nikolai Ladovsky – for the first time optical instruments were reconstructed for it, with the help of which the great architect taught his students to see a bright communist future). In the summer of 2017, the gallery opened the Museum of the Avant-Garde on Shabolovka — a constantly updated local history exposition about everyday life in the socio-architectural utopia of the avant-garde, made in collaboration with residents of the quarter and neighboring constructivist houses and housing estates, and a discussion platform with it was also a kind of utopia — the project of the Museum of Avant-Garde Architecture, which, of course, should be opened on Shabolovka, in the most densely populated district of Moscow with constructivist masterpieces.

It is common to think that the architecture of the Soviet avant-garde did not take into account the needs of real people, constructing the ideal person of tomorrow – Shabolov’s architectural exhibitions refuted this point of view, presenting evidence obtained by anthropology and oral history. However, “On Shabolovka” has always argued with generally accepted views: in “Soviet Antiquity”, the viewer learned about the existence of dissident classics in the USSR of the 1930s, which did not fit into either the Stalinist Empire style or international art deco; on “Surrealism in the Land of the Bolsheviks” I saw that the Oberiuts and artists of their circle are knocked out of all the schemes in which they try to fit the avant-garde revolutions of the interwar period “with us” and “with them”. Exhibitions about propaganda trains and IZOSTAT, about Alexei Gastev and Vladimir Mayakovsky, sustained in a revolutionary-romantic tone, sometimes seemed to replace the critical distance with nostalgia for utopia, but the typical Shabolov hero is a tragic hero, fellow traveler, renegade, outcast, marginal, pest, like the beetles and caterpillars from the Insect Culture of the 1920s-1940s exhibition, warned of the dangers of nostalgic identification with the Stalin era.

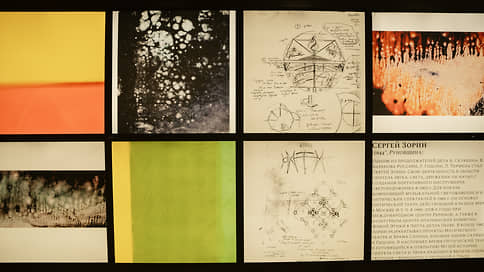

The Leningrad avant-garde artist Grigory Gidoni, who designed a monument to the 10th anniversary of the October Revolution in the form of a giant light-color-musical globe, dreamed of creating an Institute of Light and Color and was shot as a Japanese spy in 1937, is precisely this typical Shabolov hero. Little is left of Gidoni: many manuscripts, paintings, graphics, photographs, projects were confiscated upon arrest and subsequently burned by the NKVD. The exhibition “On Shabolovka”, made by the St. Petersburg musicologist Olga Kolganova, is not so much a retrospective as an exploratory homage, placing the artist among the same Wagnerians, the prophets of the total synthetic art of the future: Wassily Kandinsky, Mikhail Matyushin, Vladimir Baranov-Rossine, Alexander Skryabin, Lev Termen . In the manifesto “The New Art of Light and Color”, published in Leningrad in 1930, Gidoni, inspired by the poetry of electricity, says that it is light that will form the basis of this future synthesis. Despite the fact that most of Gidoni’s heritage was destroyed, the beam of colored light sent by him into the future was caught by the experimenters of the sixties – in the Kazan Special Design Bureau “Prometheus” Bulat Galeev began to reconstruct the “light monument” for the 10th anniversary of October. The exhibition, involuntarily summing up the eight-year activity of the Na Shabolovka Gallery, suggests that the most fragile and ephemeral art is capable of breaking through dark times like a ray of light. This gives some reason for hope.

“Grigory Gidoni and his New Art of Light and Color”. Gallery “On Shabolovka”, until September 18

Subscribe to Weekend channel in Telegram

[ad_2]

Source link